The Science Behind the Science of Change: How the Duolingo App Approaches Language Learning

On this episode of The Science of Change, host Kristen Berman talks with with Duolingo’s Head of Product Management Cem Kansu to talk about the ways this amazing app keeps people engaged and learning. For listeners who want a deeper dive into the behavioral science behind each episode, we’ve compiled and summarized the most relevant research here.

Haven’t heard the Duolingo episode on our new podcast, The Science of Change? Listen here!

A collection of research on language learning

Duolingo is a popular language-learning app and website, well-known for its supportive, engaging and slightly addictive behavioral design strategies. To learn a language, Duolingo argues, consistency is key—so we took a look at the science behind language learning.

Perceived learning is very different from actual learning.

This meta-analysis found a correlation of .34 between actual and perceived learning. This is not awful, but closer to 0 than to 1! For comparison, perceived learning correlated much more strongly with motivation to learn (.59) and satisfaction with learning (.51). Similarly, student evaluations of perceived learning in college classes don’t meaningfully correlate with actual performance.

One explanation of this involves fluency. The idea is that you base your perceived learning on how easy it feels when you learn. If it feels easy, you must have learned a lot; but if it feels hard, you must have not learned so much.

This might lead to conflict in terms of designing learning experiences.

The fluency heuristic leads to an ironic situation whereby the more you’re actually learning, the harder it feels — and thus the less you think you’re learning. And vice versa.

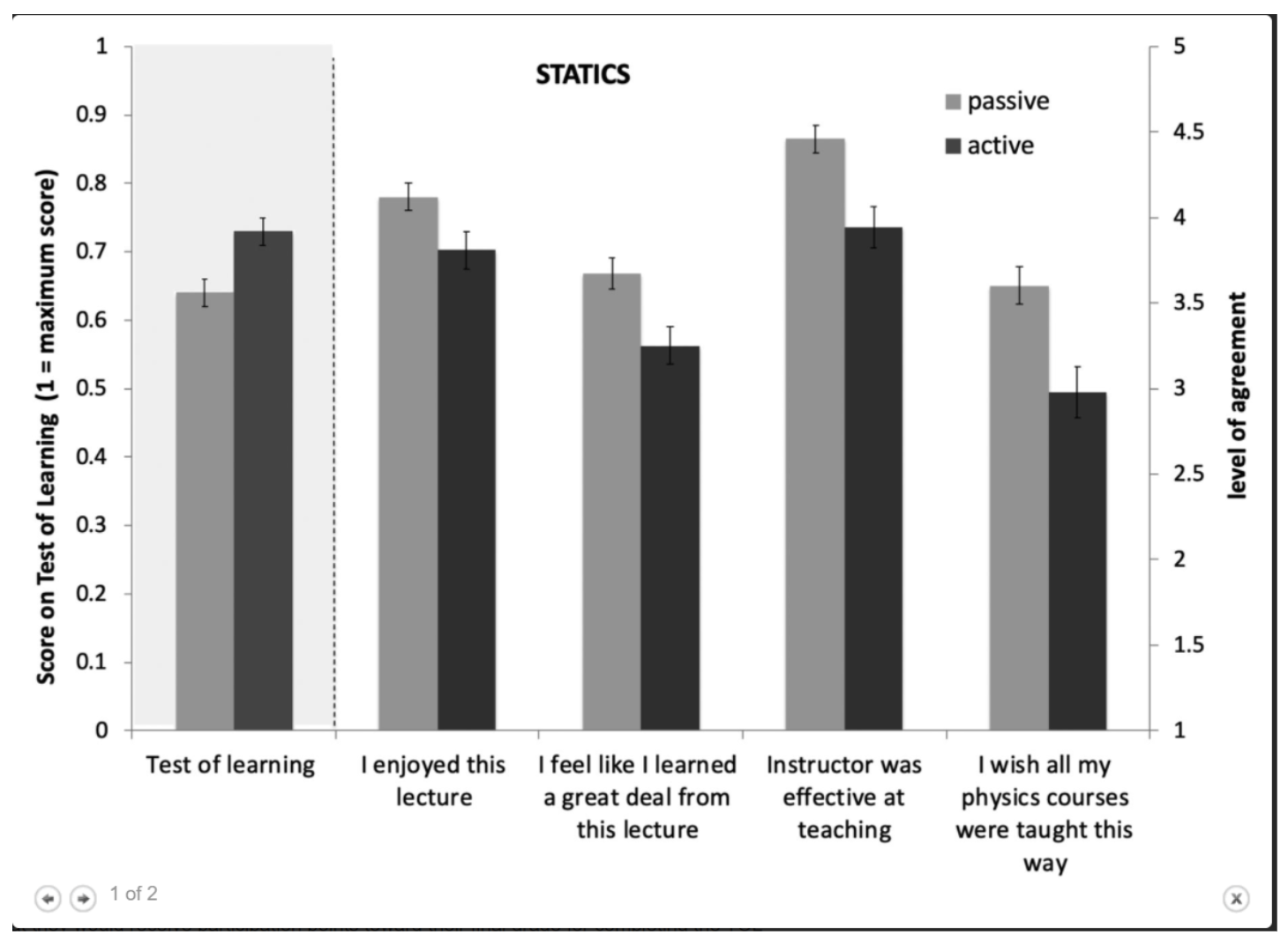

This is exemplified by a field study that randomized college classes to either active or passive learning. Active learning had a strong positive effect on learning: about 10 points on a 100-point scale! But active learning also had a strong negative effect on perceived learning and enjoyment.

This sets up an inherent conflict for learning apps: Not only do app designers need to choose between making an app that people enjoy and making an app that teaches them something—they might also need to choose between making an app that teaches people something, and making an app that people think is teaching them something.

Duolingo committed to the “fun” side of the fun/learning equation. And a common criticism is that Duolingo doesn’t teach you much — there’s a hilarious Forbes piece describing how the CEO and CRO fail at basic French and Spanish, despite having practiced these languages on Duolingo for several months.

This Rosetta Stone commercial touches on this point, trying to argue that because their product is more difficult, it’s a more effective way of learning a language.

Testing is a highly effective learning strategy.

There’s a bunch of research on testing effects, demonstrating that testing increases learning (even compared to more studying), and potentially even when feedback is not provided. For example, in this paper, middle-school students who were quizzed performed better on exams. Students who were tested outperformed students who passively reviewed the same quiz questions and answers.

This is something Duolingo does very well — they’re almost all testing, with very little teaching. The testing literature came from a very different background, though: classrooms where students only learn via lectures and reading. Those researchers were trying to make the case that tests aren’t just good for evaluating knowledge, but also for learning (implying that you should introduce regular, low-stakes quizzes into the classroom). An open question, then, is whether a platform that’s 99% testing has taken the strategy too far, and would benefit from a more balanced lesson-to-test ratio.

On a related point, what is the role of failure and errors in learning?

Presumably, one of the reasons that testing is effective is because it allows you to learn from your mistakes. With the paid version and sometimes with the free version, Duolingo can be designed to minimize error experiences (you can see the translation for each word before submitting, and you can often get the right answer from context even if you don’t know a word).

One question, then, is whether we need errors for learning, and if so, does that interfere with a frictionless, gamified, habit-forming experience?

What is the correct balance between explicit and implicit language learning?

You can learn a language explicitly (i.e. by being told how to conjugate a verb)—or you can learn it implicitly (by being exposed to a language and picking it up as you go). One heavily-cited meta-analysis shows that explicit second-language instruction was more effective than implicit instruction (although both worked).

Duolingo leans towards implicit instruction, as do most language-learning apps. In some cases, it might be more useful to learn a rule for conjugating a verb into past/present/future rather than extracting the rule from a bunch of sentences.

Want to learn how top companies apply behavioral science?

Check out the Behavioral Economics Bootcamp.

CITATIONS

Renfree, I., Harrison, D., Marshall, P., Stawarz, K., & Cox, A.L. (2016). Don’t Kick the Habit: The Role of Dependency in Habit Formation Apps. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2851581.2892495

Huynh, D., & Iida, H. (2017). An Analysis of Winning Streak’s Effects in Language Course of “Duolingo”. Asia-Pacific Journal of Information Technology and Multimedia, 6, 23-29. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:56381654

O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (1999). Doing it now or later. American Economic Review, 89(1), 103-124. https://www.jstor.org/stable/116981

Wohl, M.J., Pychyl, T.A., & Bennett, S.H. (2010). I forgive myself, now I can study: How self-forgiveness for procrastinating can reduce future procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 803-808. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55769299

Lally, P., Jaarsveld, C.H., Potts, H.W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 998-1009. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15466675

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological bulletin, 125(6), 627–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035519

Loveland, K. K., & Olley, J. G. (1979). The effect of external reward on interest and quality of task performance in children of high and low intrinsic motivation. Child Development, 50(4), 1207–1210. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129350

Metcalfe J. (2017). Learning from Errors. Annual review of psychology, 68, 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022

Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, 35(4), 989–998. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015729

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L.S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116, 19251 – 19257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Heirich, P. (2014). A/B Testing Case Study: Air Patriots and the Results That Surprised Us. Amazon Developer. https://developer.amazon.com/blogs/post/TxO655111W182T/A-B-Testing-Case-Study-Air-Patriots-and-the-Results-That-Surprised-Us

Job, M.A., & Ogalo, H.S. (2012). Micro Learning As Innovative Process of Knowledge Strategy. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 1, 92-96. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:106977629

Blanco, C. & Pajak, B. (2018). What’s the best way to learn with Duolingo? Duolingo Blog. https://blog.duolingo.com/whats-the-best-way-to-learn-with-duolingo/