Guest Post from Shea Fallick and Anoosha Kumar at PadSplit

When you live by yourself, there’s only one person to do the chores. You are taking out the trash. You are doing the dishes. You are vacuuming.

When you live with roommates, life should get easier. You can, in theory, share the load with everyone. They can take out the trash and do the dishes once in a while. They’ve got counters, and you’ll take floors. In theory, it’s all upside. What was once a one-man job is now split between multiple people.

But does it get easier? This depends.

If you feel like you’re pulling more weight than Jeremy, you may start to resent Jeremy. You see him leave his dishes out. You see him walk by the full trash. You get annoyed. If Jeremy doesn’t care about the house, why should you? If there are already 3 dishes in the sink, what’s one more?

We at PadSplit attempted to solve this hairy problem. PadSplit is a prop-tech startup that turns traditional homes into co-living rentals. We pair up strangers and these strangers share large homes together. It works because everyone is saving money by sharing space. But, it also means that this group of strangers needs to come together to clean the space.

Image: an example of PadSplit messaging, explaining the rules and their reasoning

Chore Wheels

At PadSplit, we wanted to first test the traditional approach of chore management: Chore Wheels. A Chore Wheel, in its pure and basic form, splits tasks up evenly between people in a group and then rotates the tasks that people are assigned every week or month. We wanted to know: do Chore Wheels improve cleanliness? And do participants feel like they improve fairness?

We hypothesized that Chore Wheels would not only increase cleanliness but would also increase fairness. Why? Because you’re responsible for your tasks and no one else’s. It’s clear who forgot to take the trash out. Labor is divided evenly and you don’t do more than your fair share.

But we also hypothesized that Chore Wheels could make the world feel too transactional. Imagine two spouses doing a Chore Wheel—it would feel weird to formally assign your spouse to dishes one night, and then get angry at them if they were working late and couldn’t do it. Realistically, you would remember that you’re in a marriage for the long run; one random weeknight of doing the dishes while they work late will surely be made up for in the future when you need to work late.

To discover what would actually happen with a Chore Wheel in practice, we conducted our own experiment. Before we rolled out the Chore Wheel to all of our rental properties, we wanted to test our intuitions and understand the impact it would have on both cleanliness and fairness.

How it Worked: The Chore Wheel Experiment

We divided the PadSplit houses. Half of those houses were marked “control.” The “control” houses didn’t get a Chore Wheel; all we did was collect data about their behavior The other half of the houses were assigned to the “test” condition. For these houses, we introduced a Chore Wheel.

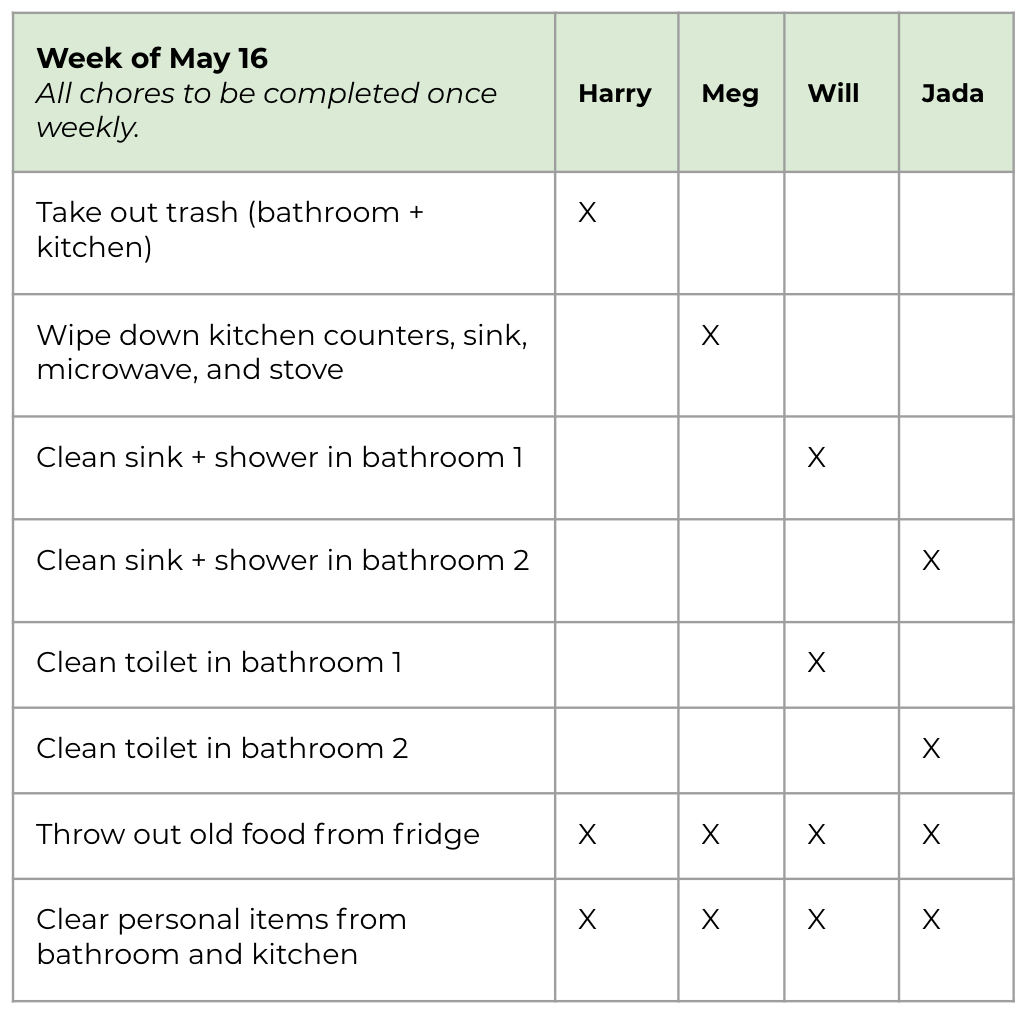

Some PadSplit houses have House Leaders. This person serves as a liaison between PadSplit and the members of their homes by monitoring cleanliness, welcoming new members, and submitting maintenance requests. Each House Leader was given instructions on how to set up the Chore Wheel, using templates and an interactive training session. We asked them to get input from all the roommates in their house and collectively pick the chores that would be divided up on the wheel. We provided a list of sample chores to help with this task, but house leaders were ultimately responsible for picking the chores and assigning.

Image: A visual example of the Chore Wheel

What Happened?

Our goal was to get a reduction in negative support tickets and improve member ratings related to cleanliness. Basically, we wanted to reduce the number of people complaining to us that their roommates didn’t take out the trash (or do the dishes, or vacuum, etc.).

Did the Chore Wheel increase cleanliness? Yes. Our Bayesian A/B analysis showed a positive signal for the Chore Wheel, reporting a 99% chance that the test group performed better than the control. In test homes, we found a 49% expected reduction in support tickets or negative member ratings related to cleanliness.

In addition, we conducted surveys with the house members. The survey results suggested the Chore Wheel had an impact on cleanliness in homes—65% of housemates in test homes felt their house was clean or very clean vs. 55% of housemates in control homes.

How Chore Wheels Make People Feel

However, when we look at how this Chore Wheel made people feel, the picture becomes less clear. In general, the Chore Wheel was supposed to more evenly distribute labor between all housemates. This may have happened, but that’s not how it felt. Instead, in homes with a Chore Wheel, about half of House Leaders felt that they did more than a quarter of the share of chores (way more than what would be an equal distribution). In the control homes, only 31% of the surveyed members felt that they did more than a quarter of the chores. What’s happening?

It could be that the Chore Wheel is making House Leaders pick up the slack for their roommates, and actually do more work than before. But what’s also possible is that the House Leaders are doing the same amount of work as before (way more than others!), but the Chore wheel calls their attention to this chore imbalance. Now, instead of washing the dishes as a favor to their roommate, the house leader realizes that Jeremy should have done the dishes and didn’t do them. Jeremy bailed on his chore. With a visual representation of their work, it doesn’t feel like a favor anymore for the house leader to pitch in, it feels like… a chore.

What Can We Learn?

The Chore Wheel is a rational way to divide labor amongst housemates. It seems to keep homes a bit more tidy. During interviews, people mentioned that the Chore Wheel was typically effective at motivating 1 or 2 more house members to start cleaning who hadn’t been great at cleaning before. Of course, that isn’t a very high hit rate, but when 1 or 2 more people are doing the dishes, this can make a real impact!

But, it also may come at a cost. We may be displacing the natural energy of people in a home to help their roommates collectively clean up by formalizing our behavior. The potential downsides to this phenomenon are well-documented in behavioral science research. One particularly famous study comes from a nursery school in Haifa, Israel where daycare workers began imposing fines on tardy parents to encourage on-time pickups. Daycare workers assumed that parents would arrive on-time to avoid fines, but the fines were quite small (just a few dollars), and actually increased late pickups, by allowing parents to just rationalize the cost as part of the daycare service. They had inadvertently transformed a social norm (guilt about being late) into a market norm (the cost of doing business). When daycare workers took away the fine, parents did not revert back to their original behavior, arriving later than ever.

Future Chore Wheel Tests

Understanding the unintended consequences of behavioral interventions, we’re using a nuanced approach. For now, PadSplit will continue testing Chore Wheels and monitoring the feedback. Anecdotal accounts from interviews suggest that new members in the homes were much more receptive to the Chore Wheel than older members. Our future tests will look at how we set norms immediately upon move-in that reinforce the value of cleaning. And of course, we want to help people feel better about the chores they do. We believe that by acknowledging people’s efforts, we can help make people feel great about their contribution—and their housemates.

Want to learn practical applications for behavioral science? Check out the Behavioral Economics Bootcamp.