This project is a part of Duke’s Common Cents Lab. The Common Cents Lab is funded by the MetLife Foundation and supported by Blackrock as part of BlackRock’s Emergency Savings Initiative. This was first published in the 2020 Common Cents annual report. The project was done in collaboration with the Irrational Labs team, led by Richard Mathera and Lindsay Juarez.

Background: Does Budgeting Help You Save Money?

Among financial educators and within personal finance circles, budgeting – both tracking expenses and planning how much to spend in a specific category of expenses – is heralded as a way to reduce expenses and focus spending on areas of personal importance.

However, much remains unclear about the best ways to structure budgets, as well as how to help people adhere to them. Furthermore, the extent to which budgeting actually helps people to reduce expenses even in the short-term, let alone in the longer term, is equally uncertain, especially given the behavioral challenges associated with creating and adhering to a budget.

The experiment explored how people approach and use budgets to guide their financial behavior. We developed an experiment to explore whether traditional-style budgeting is effective at changing behavior and how we might use findings from behavioral research to improve budgets. As with all Common Cents Lab projects, the partner provided an anonymized data set for this project.

Hypothesis & Key Insights

We began to research budgeting first through in-person interviews and auditing financial education courses. We wanted to learn how people think about budgets and how efforts to encourage budgeting suggest that people begin using them. We also conducted online surveys and analyzed engagement and behavior through the app.

This background work highlighted several behavioral challenges that people face when budgeting:

- Just sitting down and thinking through a budget requires significant self-control and time. Getting started on a budget is a daunting activity and procrastinating is easy – busy people already find it difficult to carve out time for things that they actually want to do.People easily push off the planning until tomorrow, and then six months have passed with no progress. Once a person has undertaken the seemingly monumental task of creating a budget, the self-control struggle has only begun since they then must actually adhere to that budget.

- Creating a budget and adhering to a budget requires combatting information aversion. Budgeting forces a person to take stock of previous financial decisions and reflect on life decisions that might be unpleasant to revisit. On top of that, when someone does not follow their budget, chances are high that they do not want to be reminded – or worse, feel shame – that they did not spend their money as planned.

- Creating a budget also requires fighting inattention and forgetting. Once a budget is actually created, a person must remember how much spending is allowed in a particular category over the budget period. They must also track and be able to recall how much has been spent so far across all categories for a month (or more) at a time.

Experiment

We worked with a popular fintech app to develop and test three different approaches to budgeting.

We randomized 9,035 people into one of three conditions: 1) Informational Control (N = 4368); 2) One-Number Budgeting (N = 2723); and 3) Category Budgeting (N = 1944). We initiated the experiment September 30, 2019 and ran it for 13 weeks.

To eliminate selection bias, we showed Android users the same tile screen, prompting them to “Take control of your budget.”

Those users that clicked this tile were opted into the budgeting experiment and were randomized into one of the three budgeting conditions. The conditions were as follows:

Condition 1 / Control

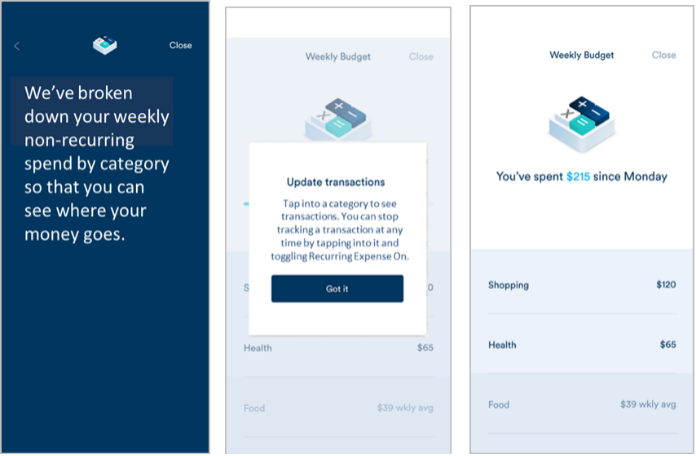

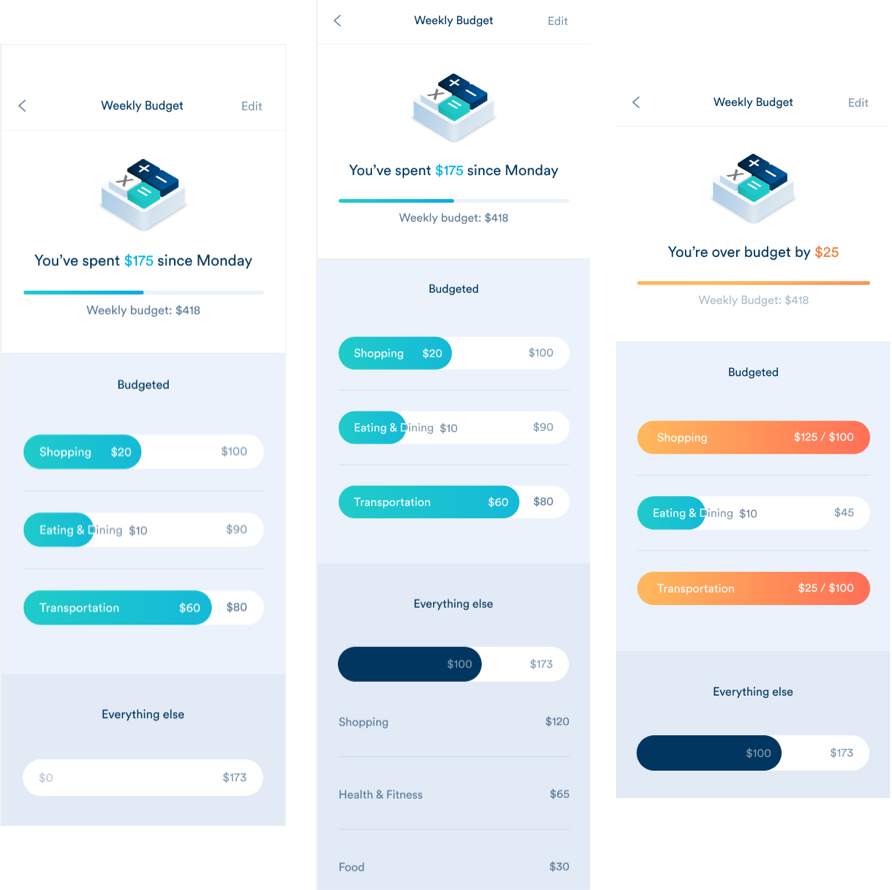

This was an informational control where people are presented with a sum of their overall weekly spending, broken down into transactions by category.

Condition 2:

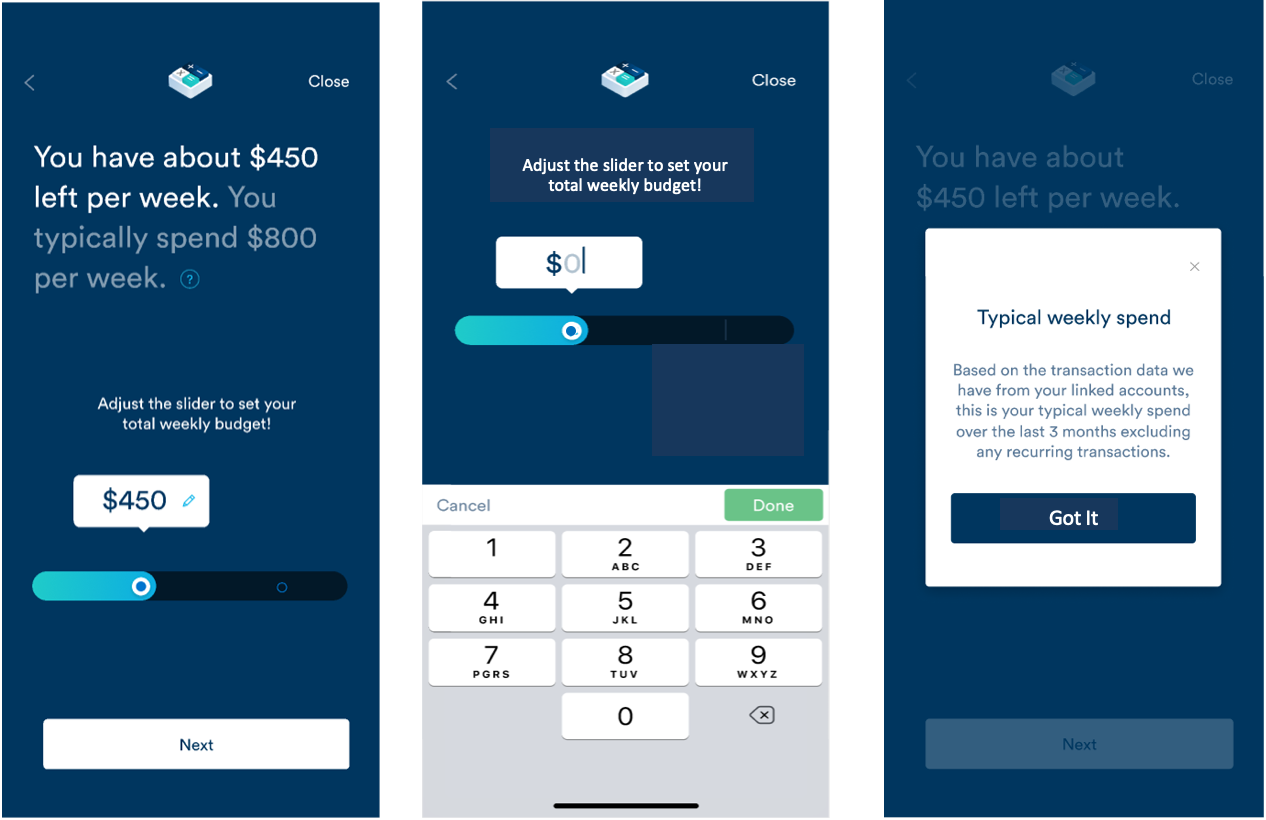

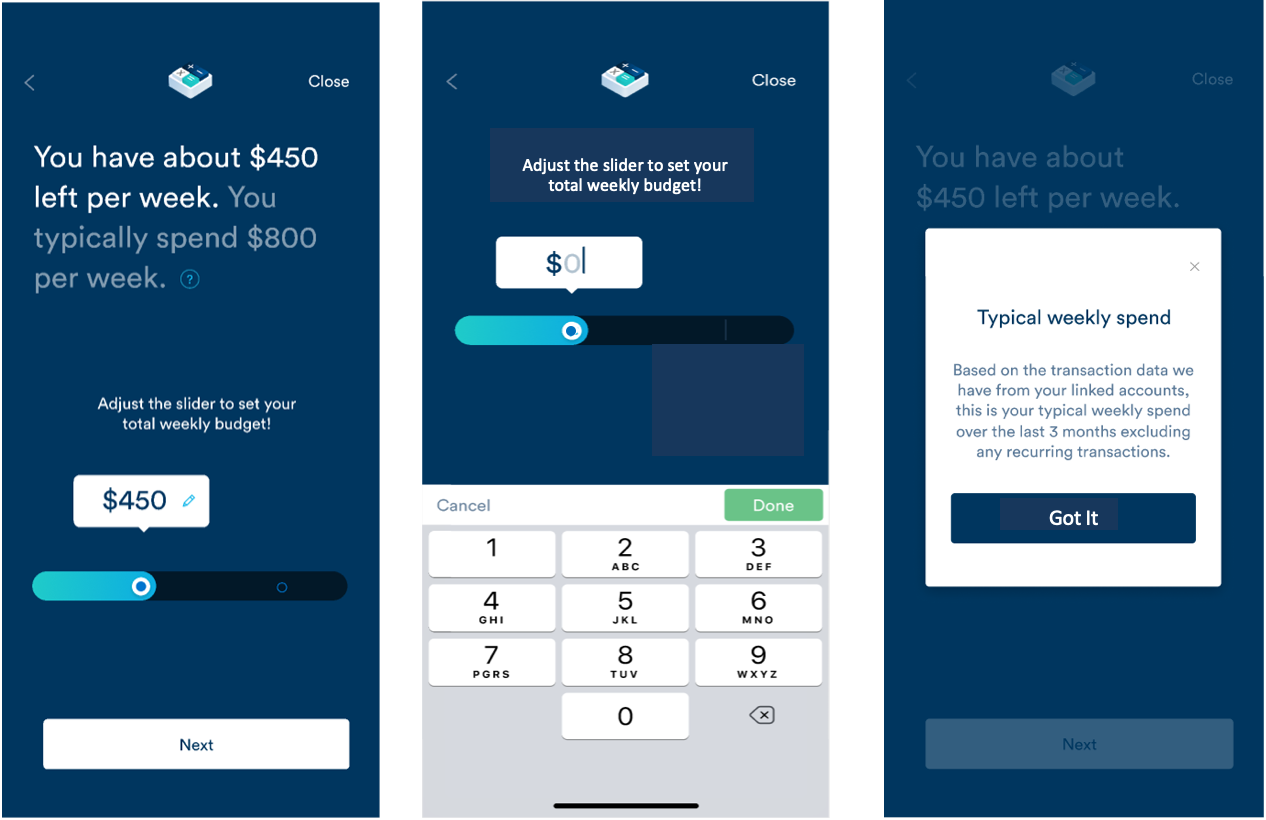

This was an “overall budget-setting” condition where people are guided to set up a one-number budget for the week.

Setting the Budget

Money Feature Details View

Condition 3:

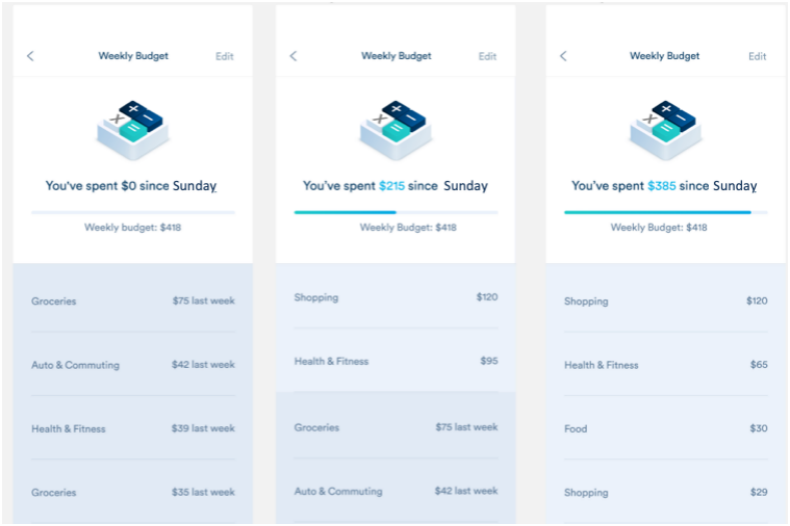

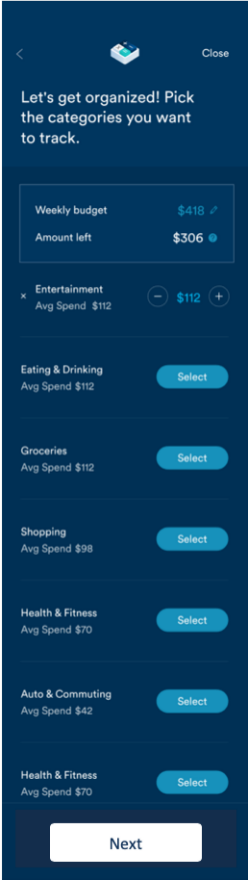

This was a “category-by-category” budget setting condition where people are prompted to set up an overall weekly budget number then to select specific categories of expenses to set goals for.

Setting the Budget

Money Feature Details View

We tracked how budgeting affects subsequent spending behavior to see if budgeting helped participants to reduce their expenses more than an informational control.

Results of Budgeting Study

Although some differential drop-off occurred due to effort between conditions, budgeting inherently requires some level of effort and active participation. For example, in a hypothetical two-condition paper-and-pencil budgeting intervention which placed people in two separate rooms — one in which people are asked to complete a budget, and one in which they would be asked to wait or perform some other activity such as reflection — someone who did not lift a pencil to participate in the budgeting experiment would not be considered to have budgeted.

The budgeting experiment that we conducted randomized someone’s chances of being placed in one of the three conditions due to the identical opt-in screen. The feature lowered the amount of effort required to participate in budgeting as low as reasonably possible with pre-populated budgeting options. There were no observable pre-existing differences between the budgeting groups on income or spending patterns.

Engagement With the Budget

In terms of engagement with the budget, about 10% of the users in the experimental condition saw the budget 8 times or more, while a majority of the users (84%) saw the budget 5 or fewer times over the experimental period. Both budgeting variants statistically significantly increased engagement over the control from once every 4 weeks to once every 3 weeks (p < 0.001). In all conditions, engagement declined over time.

Main Finding

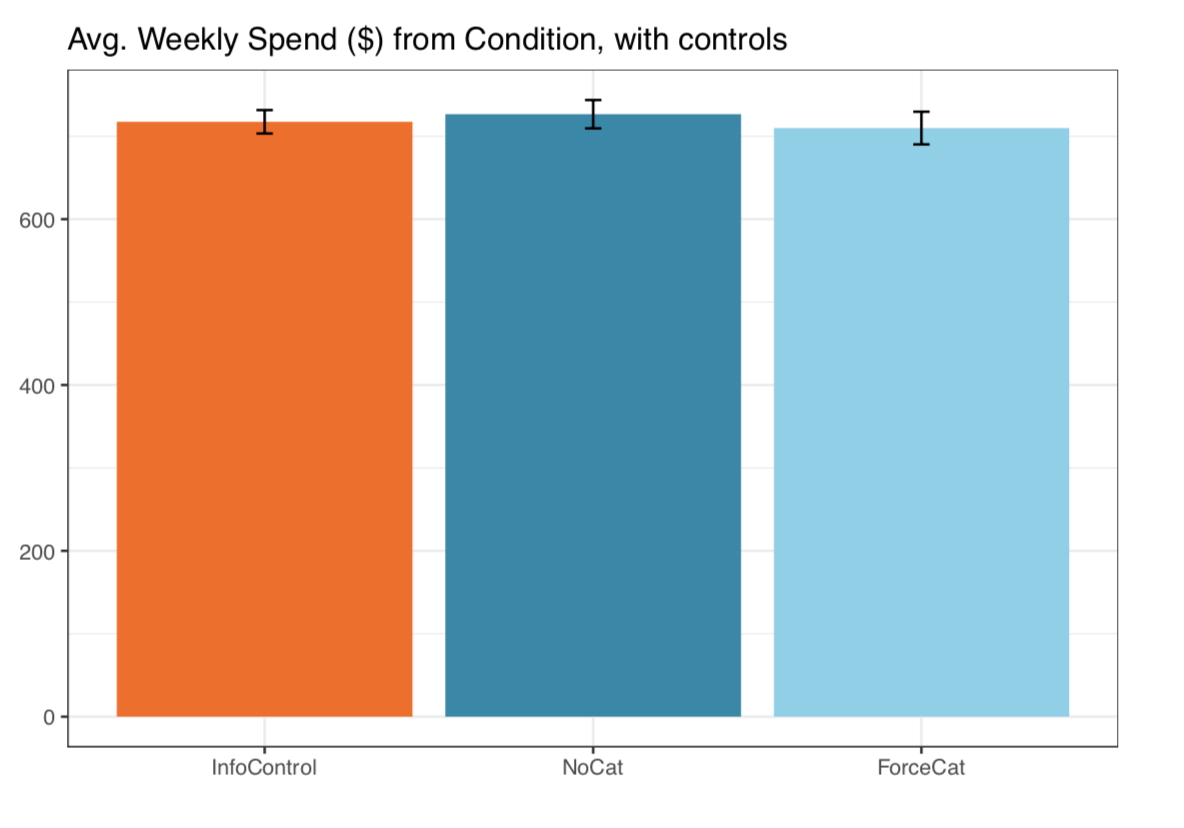

Overall we found no significant difference between the average spending of the control group ($675.97) vs. the single budget ($681.08) or the category condition ($673.25), (ps > 0.4).

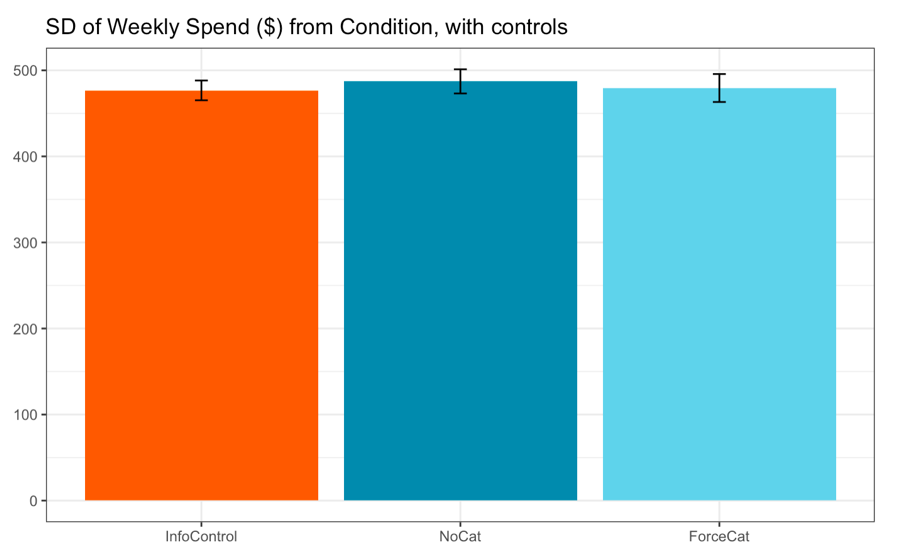

We also found no statistically significant difference in the variability in spending across conditions.

More Insights on Budgeting

- Budgeters generally overspent the amount they budgeted, spending 1.3-1.4 times what they intended.

- We did not see evidence that budgeters reduced their spending relative to their historic spend (ps > .15).

- We did not see spending differences by condition when we examined only the most frequently budgeted spending categories (food, groceries, shopping, and transportation) (ps > .5).

- Even after controlling for usual spending patterns, we found that spending in a budgeted category was about $30 higher than spending in non-budgeted categories (p < .001). We found no differential impact for users that checked their budgets more frequently (ps > .1).

So while the budgeting feature increased engagement with the app, overall we did not find positive or negative financial impacts from budgeting.

But there is some good news!

There are proven strategies that can help us effectively manage our money. We summarized four alternative strategies you can use instead of budgeting. Read about them here.

Want to learn more about behavioral design? Join our Behavioral Economics Bootcamp today.