Over 90% of people think a budget will help reduce their spending. Sadly, they are wrong.

In theory, budgeting makes sense. If people know how much money they have and set a goal for how much they want to spend (or save!) – then the next time they’re tempted to get takeout for lunch instead of eating their PB&J? It’s the rational decision to prioritize the budget and not spend.

We’ve probably all been through this exact situation – and ended up with the takeout. Rest assured, it’s not just you! In fact, when we partnered with Common Cents Lab to run a study with thousands of fintech users and real budgets across 3 months? We found no evidence that budgets helped people spend less.

We hate to say we told you so, but there’s more to fintech product design than just optimizing for ease of use. And that’s where behavioral science comes in. So, keep reading to learn about 4 behavioral science principles every fintech should know and design for.

Principle #1: Optimism Bias

Long-term financial health requires planning for the future. So, what’s the issue there?

Two words: optimism bias. Our mind’s eye is blurry. When people project into the future, they don’t fill in the details – which means they believe they’ll be less busy, more responsible, and more thrifty.

But in reality, people consistently underestimate their weekly expenses. In our own budgeting study, people set budgets about 25% lower than their usual spending habits. Maybe they were setting an intentionally ambitious goal, but actually cutting 25% is a level that gets you written up in NYT articles about the FIRE movement. In other words, it takes intense planning. And for most people, being too optimistic about their ability to save means not saving enough.

Pro Tip: Help people get realistic about their spending – and their ability to save.

In this context, ‘getting realistic’ requires knocking that well-behaved future self off the pedestal – and filling in the details of where and how money actually gets spent.

Even though it’s counterintuitive, it turns out that asking people about what might come up unexpectedly can help them fill in actual mundane expenses that come up consistently.

Principle #2: Present Bias

Ever decide to splurge on a purchase – even when you knew you should have put the money into savings? That’s present bias.

Present bias is the human tendency to overvalue the ‘here and now’ in making decisions, discounting the future and potential consequences. So the idea of long-term financial health? It requires fighting against every innate urge to spend money now.

Balancing ease of access with reasonable safeguards is a tightrope all financial services must navigate. ‘Buy now, pay later’ and earned wage access products (‘pay on demand’) are great examples of financial services that help people bridge spending gaps and address emergencies. But they might also tempt people into spending too much.

More frequent paydays are also associated with greater spending – even after controlling for objective income levels. Because here’s the thing: people feel wealthier and spend more when they get paid – so more paydays means more days feeling flush. In one study, for example, 84% of participants accepted when offered the option of smaller, more frequent paychecks.

This shifted them from an average of 5 paychecks to 13 – with spending increasing in lock-step. The takeaway? It’s hard to resist spending easily-accessible money.

Pro Tip: When people allocate money for explicitly long-term reasons – like retirement accounts – keep it on a metaphorical high shelf (‘out of sight, out of mind’).

Don’t include long-term balances in a top-line, account summary wealth calculation. Instead, keep that balance limited to fungible accounts like checking. Even better? Calculate a ‘safe-to-spend’ amount that preemptively subtracts standing charges like rent and subscriptions.

And if you offer earned wage access or ‘buy now, pay later’ services? Be careful about the framing of your product – and how prompts and push notifications can create extra temptation for users.

Principle #3: Pre-commitment

If having an influx of cash means you’ll want to spend it all, what do you do? Tie your hands by planning ahead! That’s right: locking money away is a great strategy to ensure that it stays in your savings account.

Delays and restrictions can help someone pause in the middle of an impulsive decision – and make the calmer, longer-term choice that their more rational self would prefer. For instance, Common Cents Lab worked with Self-Help Credit Union to design a savings account that required a 24-hour ‘cooling off period’ for withdrawals. Although users reported being tempted, they were also grateful. Case in point: one standout review of the account came from a user cheerfully reporting, ‘(it) keeps the money safe. From who? From me!’

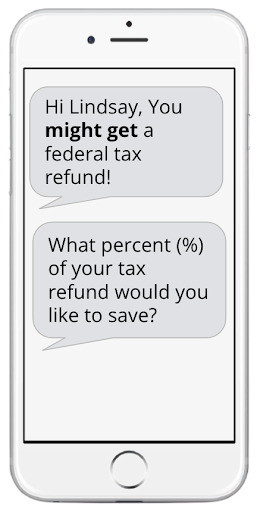

Pro Tip: Ask people to save money they don’t have yet.

In another example of getting ahead of temptation, we asked Digit users to save a percentage of their tax refund. About 10% of people said yes to saving, but the real trick revolved around when we asked. If we asked people ahead of time, back in February, they wanted to save much more of their refund (27%) than if we asked in May (17%). The lesson here for fintech product design? It’s much easier to resist temptation when it’s not staring you in the face.

Principle #4: Information Aversion

If you’ve ever avoided stepping on the scale or checking your bank balance, you already know about this last bias. Information aversion drives us to avoid learning (or confirming) information we think will be bad news. For example, in our budgeting study that opened this article, we found that the average user looked back at their budget only once every 3 weeks.

You might be thinking, ‘But aren’t behavioral scientists always saying information isn’t enough to change behavior?’ And if so, touché. Some information and feedback is necessary for people to understand how to change – but a dashboard full of charts, graphs, and stats isn’t going to help most people. Only the most expert and analytical of users will be able to interpret such information, leaving most people to turn away – or simply not know how to turn the numbers into action.

Pro Tip: Think of what people should do, and then give feedback that guides without overwhelming or demoralizing them.

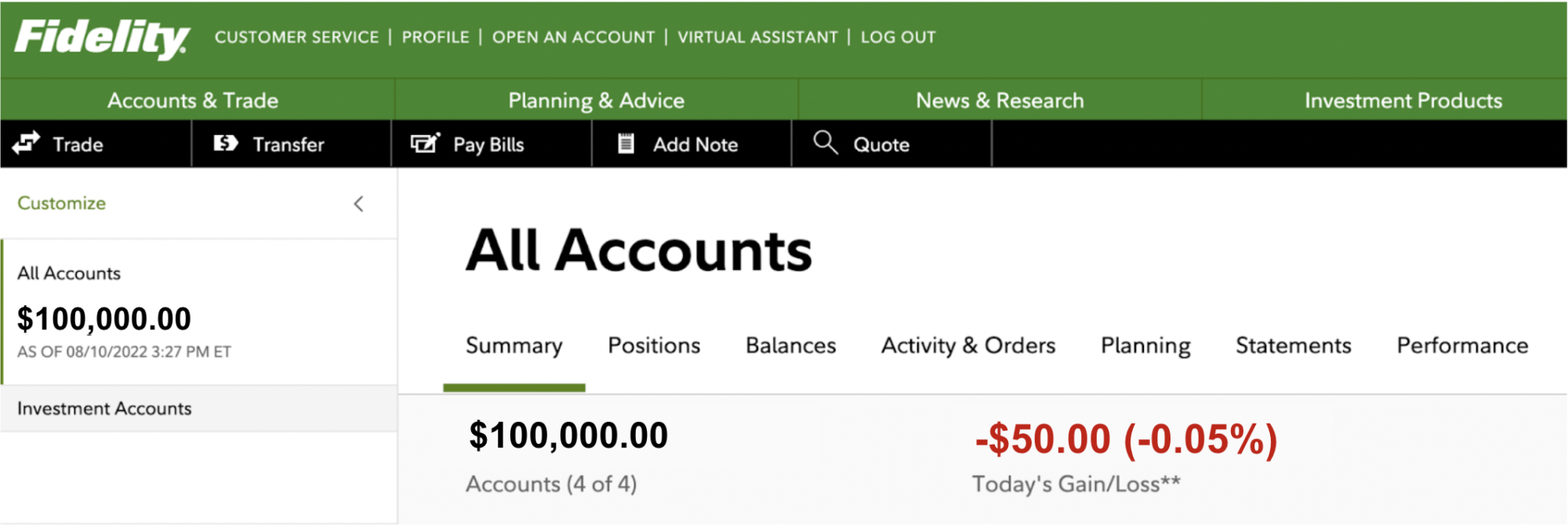

Let’s take Fidelity as an example here. If you log into your account, the largest, most highlighted number you see is today’s gain or loss. They show the absolute value (in dollars) and the percent. If it’s a negative number, it shows in red – even if the percent decline is small.

We’d argue that this creates unnecessary alarm, especially for long-term investments. Only on a later screen – after a fair amount of clicking and digging – do they show information that, overall, you’re doing well.

The feedback above is more likely to help people stay the course with long-term investments, rather than make rash decisions and move money around based on a single day’s performance.

Wrapping Up: Fintech Product Design is Better with Behavioral Science

All in all? If you work in fintech product design, you’re in the business of behavior change. You’re trying to get your users to do ‘x’ – and in the domain of financial decision making, ‘x’ is often hard.

But, you’re in luck! Behavioral science offers a shortcut – a ‘cheat sheet’ – of what drives our decision making. And these insights can help you nudge positive financial behaviors and improve financial outcomes for your users. What’s not to love about that?

Need help applying behavioral science to improve your product? Get in touch to learn more about our consulting services. Or learn more behavioral science by joining one of our bootcamps.