There is a general discomfort brewing around the increased use of our mobile devices. The word “smartphone addiction” has casually entered our lexicon, and digital detox retreats are a real thing. Articles that try to help reduce phone use are a dime a dozen, giving tactics such as turning the phone greyscale, or using a Pomodoro for focus time. Most recently, Nir Eyal, author of Hooked, has, in an ironic twist, published a whole book on how each of us can proactively reduce the grip of mobile devices on our life.

While that sounds logical at first glance, it mistakenly puts the burden on the individual to stand alone and fight off the endless attackers of their attention. A strategy that primarily relies on the individual to proactively make changes is insufficient and set up for failure.

Why? For one, such a strategy incorrectly assumes most people can predict what their future self will do, and given that prediction, take action to ensure they align their behavior with their intentions.

This is too difficult. Humans have been shown to have time-inconsistent preferences. While we may want to study later tonight, when we actually get home, the thing we most want to do is watch Netflix! In the present moment we are highly motivated by immediate rewards (for example watching TV or using our devices) and undervalue rewards that come in the future (for example, being well-rested or getting a good grade).

Some people can commit to a course of action that reduces future opportunities for procrastination or overconsumption. In behavioral economics, this is called sophisticated behavior. However, most of us are not Sophisticates. Most of us fail to realize that we will be tempted or will lack self-control in the future. We are called Naivetes. We say we’ll eat healthy, but when faced with a burger or salad, we opt for the burger.

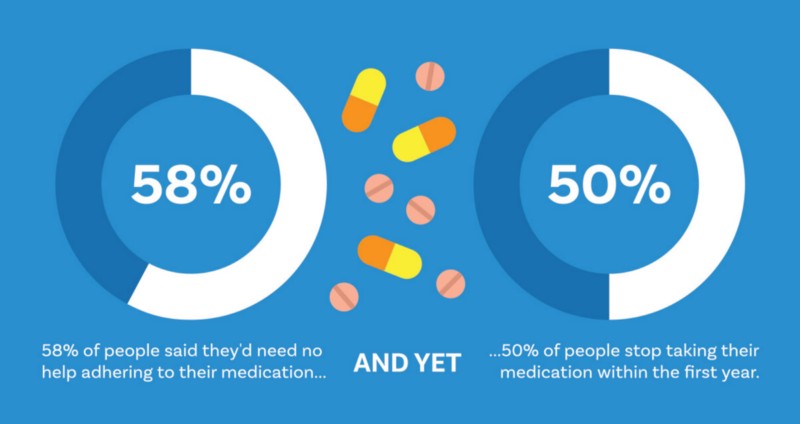

Irrational Labs surveyed 900 people and asked them to imagine they were diagnosed with a disease that would require exact daily adherence to medication. Not adhering would put them at risk for severe health complications. 58% of the respondents said they would need no help in adhering to their medication perfectly. Research within hypertension, a diagnosis that requires strict adherence shows this is not the case. 50% of the people who are prescribed hypertension medication stop taking their medication entirely within the first year!

So while people want to take their meds regularly, they do not predict that taking their medication will be difficult. Thus, they do not take action to put in place mechanisms that would help them better adhere to it.

The same can be said for device usage. Because people do not predict they will need help controlling device usage, they do not put in place self-control tools that could help manage usage. Some Sophisticates may add screen time limits, but most of us Naivetes do not. Furthermore, screen time limits, at least as currently designed in iOS, can be overruled. We’re given the option to choose: respect the limit we set or ignore it. Each instance of this taxes our self-control, which is a limited resource.

Given this, the biggest opportunity to move device usage in line with a user’s intentions falls on the designers of the systems. Behavioral science has shown that changing the environment can change behavior. Instead of convincing someone to eat less, make the plate smaller. Instead of convincing someone to care about their future, auto-enroll them into retirement savings. Instead of educating someone about eligibility requirements for federal financial aid for college, make the form easier to fill out or make it the norm to apply.

Instead of convincing someone to use their device less, design the device so it is used less.

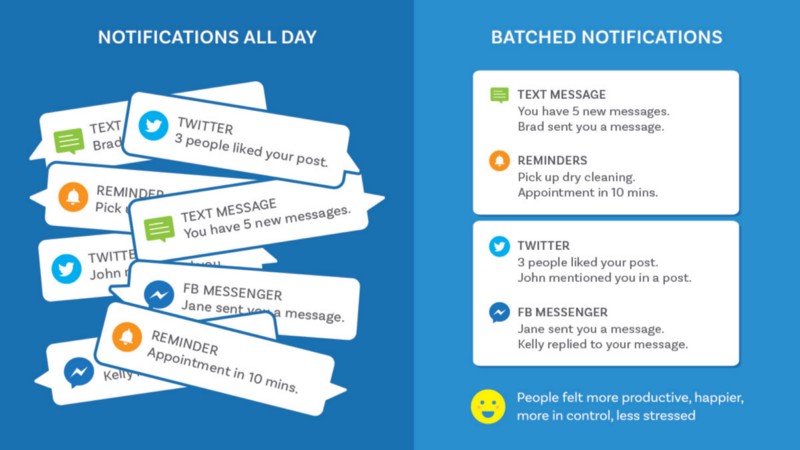

Here’s an example — Interruptions are costly: it can take around 25 minutes to get back on track with a task after an interruption. And even in a social context, interruptions are not ideal. It doesn’t feel good when the person we’re hanging out with keeps looking at her phone. So in theory, we should all put away our phones while we are working or when we’re socializing with others. But do we do this? No. Daywise is an Android app that helps address the problem of notification interruptions.

Daywise batches notifications for you. Instead of getting a steady stream of notifications throughout the day, Daywise users receive notifications in a batched grouping. Most importantly, this system works. In a study they ran in collaboration with Duke University, they found that batching notifications into 3 sets per day made people feel more productive, happier, more in control, and less stressed compared to a control group that did not have their notifications batched. Daywise understands the burden cannot fall on the individual and instead has designed a system that accounts for human nature.

In the media, this issue of responsibility for digital wellbeing is sometimes being framed as binary: it’s either on the individual or it’s the responsibility of tech. We believe that it can and should be both, and we also believe that the system design has an outsized effect and should therefore be prioritized.

Let’s take an example from Johan Hari, who recently compared people in Copenhagen vs. people in Lexington, KY. The obesity rate is very low in Copenhagen and very high in Lexington. Is this a function of a significant difference in who these people fundamentally are? Do people in Copenhagen simply have much higher levels of self-control? Are people in Lexington just lazy? Of course not. Copenhagen is one of the best bicycle friendly-designed cities in the world, such that most people there bike to work. It’s just the easiest option for them. And healthy food is abundantly available. Lexington is the opposite: it’s set up for driving, and healthy food is hard to come by. Can someone in Lexington work hard to eat healthy food and get enough exercise? Of course.

This is not a negation of individual agency and responsibility. It is a recognition, however, of the powerful effect that system design has.

Just as city planners have a responsibility to think about how their city design and programs affect their citizens’ well-being, mobile apps and our current marketplaces (Google, Apple, Amazon) have the same responsibility to think about their users’ well-being.

Like what you read? Give us a👏 !

Authors: Evelyn Gosnell and Kristen Berman

Are you a product manager, designer, or marketer? Learn how to apply behavioral insights to build products that customers love with the Behavioral Economics Bootcamp.