Americans have a drug problem: we don’t take our prescriptions. In fact, 50% of people stop taking their high blood pressure medication within 1 year of getting it prescribed. This doesn’t mean they forget to take it once in a while—it means they’re not even picking it up from the pharmacy. In the case of high blood pressure (heart disease), this significantly spikes the risk of death.

But it’s not just heart disease. Increasing medication adherence is the single easiest way to extend the life of millions of Americans. In terms of health outcomes, getting to 100% drug adherence would have more impact on public health than any improvement in specific medical treatments.

So why don’t we take our meds?

The classic research assessment would require a deep dive into the patient’s beliefs. Do they not understand the treatment plan? Do they not care about their future health? Do they not trust the doctor?

All that may be true, but it’s not why we don’t take our medication.

The Real Reason(s) We Don’t Take Our Meds

To understand why we don’t adhere to our prescriptions, let’s do a reverse thought exercise. Imagine you wanted to intentionally design a pill that no one would take. How would that look?

- You’d put it in a hard-to-open box

- You’d make the name hard to pronounce and unrelated to the name of the disease

- You’d require that people take it under specific conditions (e.g., with food and water)

- You’d give patients no feedback about whether the medication was working (except 1-3 years down the road)

Sound familiar? It’s no surprise that we miss doses.

Medication Recall: Why We Trip Down Memory Lane

If you ask a patient to name the last medication they were prescribed (or even the one they’re currently prescribed), odds are they can’t. And they’re not alone.

According to research, more than half of all primary care patients in the US can’t accurately recall critical information about the prescription drugs they take. But are we surprised?

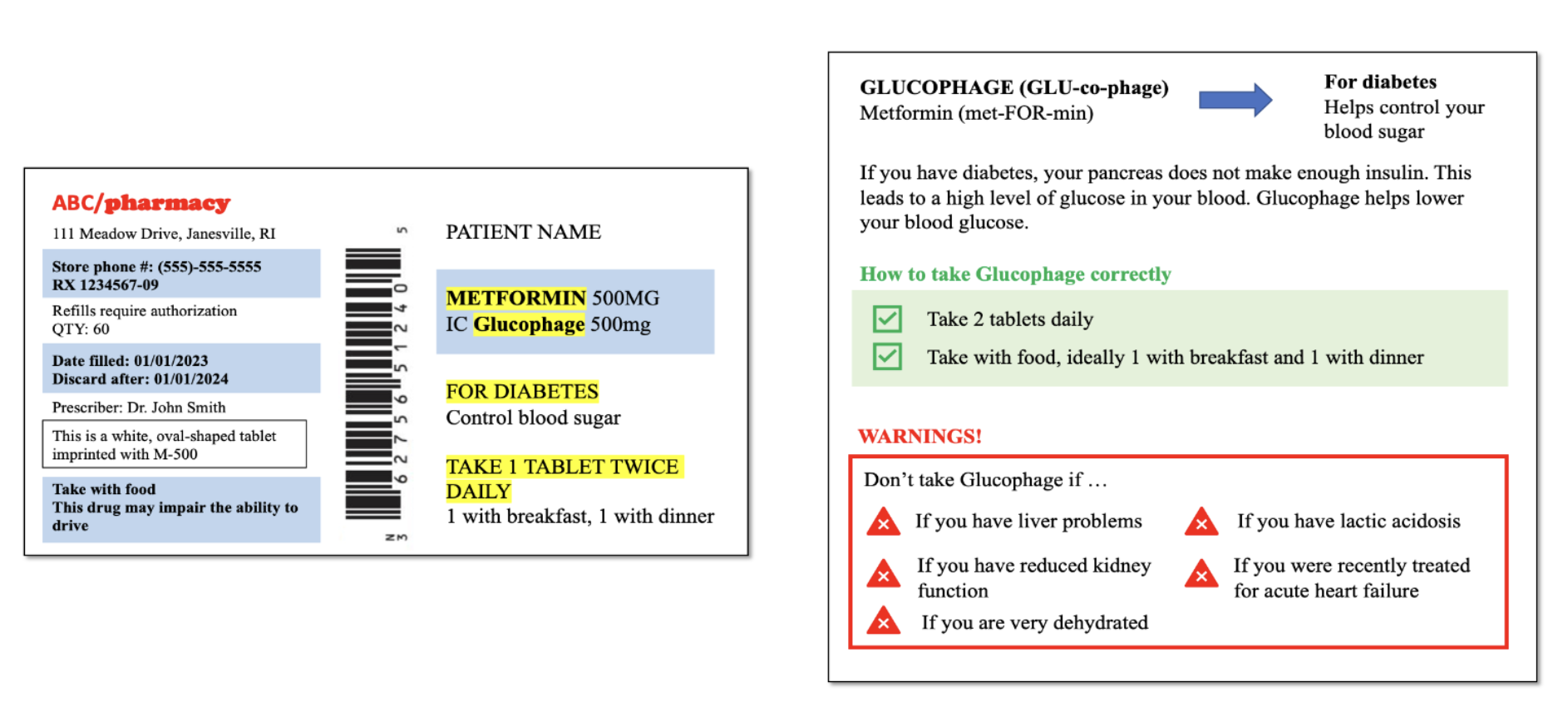

Just look at your standard prescription label.

How Researchers Have Tried (& Failed) to Solve This

Existing research tends to focus on patients’ individual deficiencies, like low health literacy. And few studies have tested interventions to improve medication comprehension.

For those that have, common interventions like simplified language, larger font, highlighting, and icons for prescription labels have had mixed results. Some studies show null effects and others (like this one) show small effects.

Irrational Labs set out to change that.

Our Experiment: Challenging 2 Key Assumptions About Medication Recall

So how would you do this? Great question. Using behavioral science as our guide, we decided to test two approaches:

Approach 1: Make It Easier

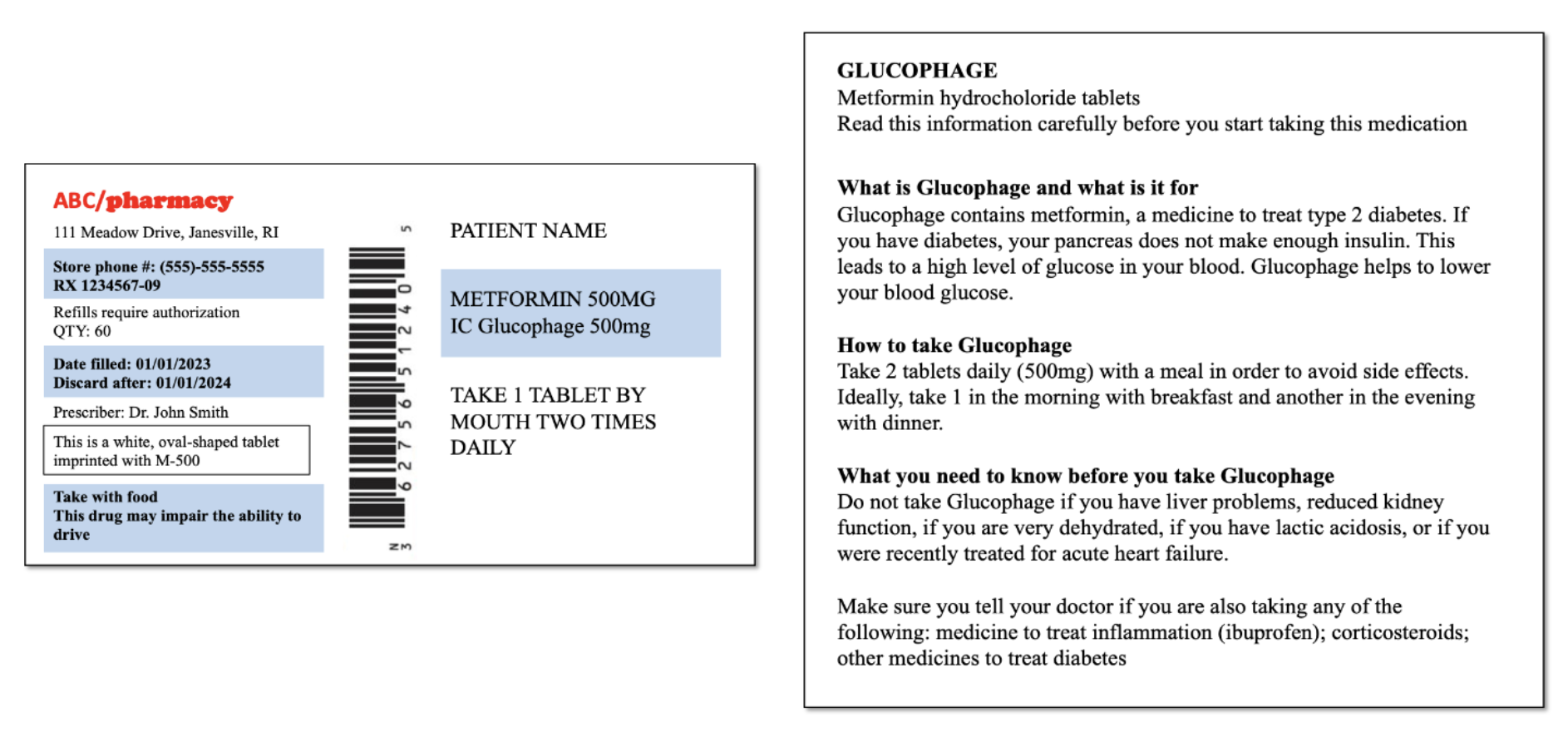

Prior research suggests that giving people the ‘gist,’ or the bottom line, helps memory. Our ‘gist reasoning’ condition simplified the label by providing summaries at the top.

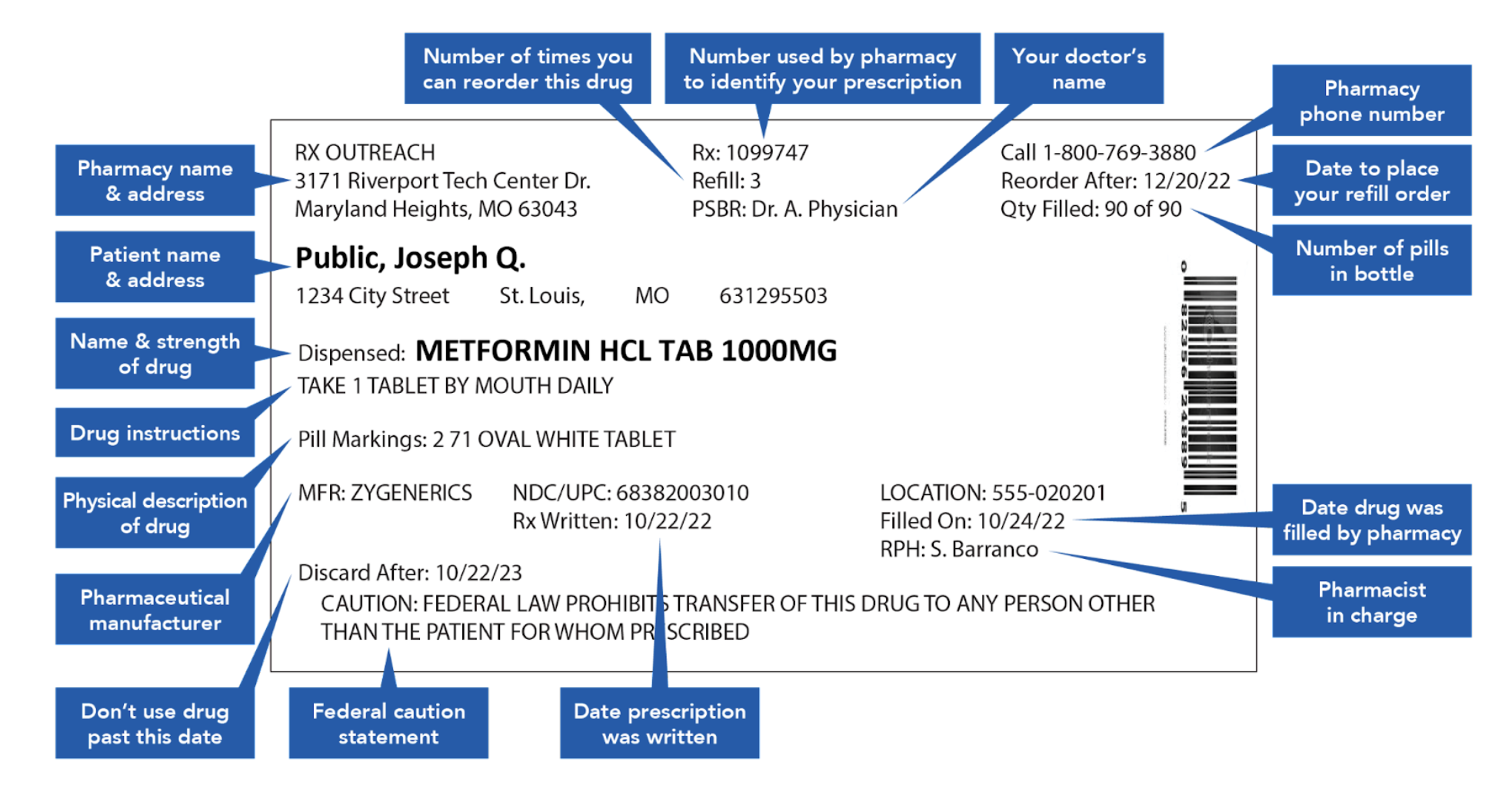

From this:

To this:

Similarly, our ‘formatting & chunking’ condition used icons, simplified language, and highlighting to reorganize the labels into more readable chunks:

Approach 2: Make It Harder

Our second approach was to add friction. In this case, ‘good friction.’

When it comes to consumer and patient experiences, we typically want to remove friction. However, well-timed friction, though it may seem counterintuitive, can also have a positive effect (like decreasing misinformation on TikTok). This is ‘good friction.’

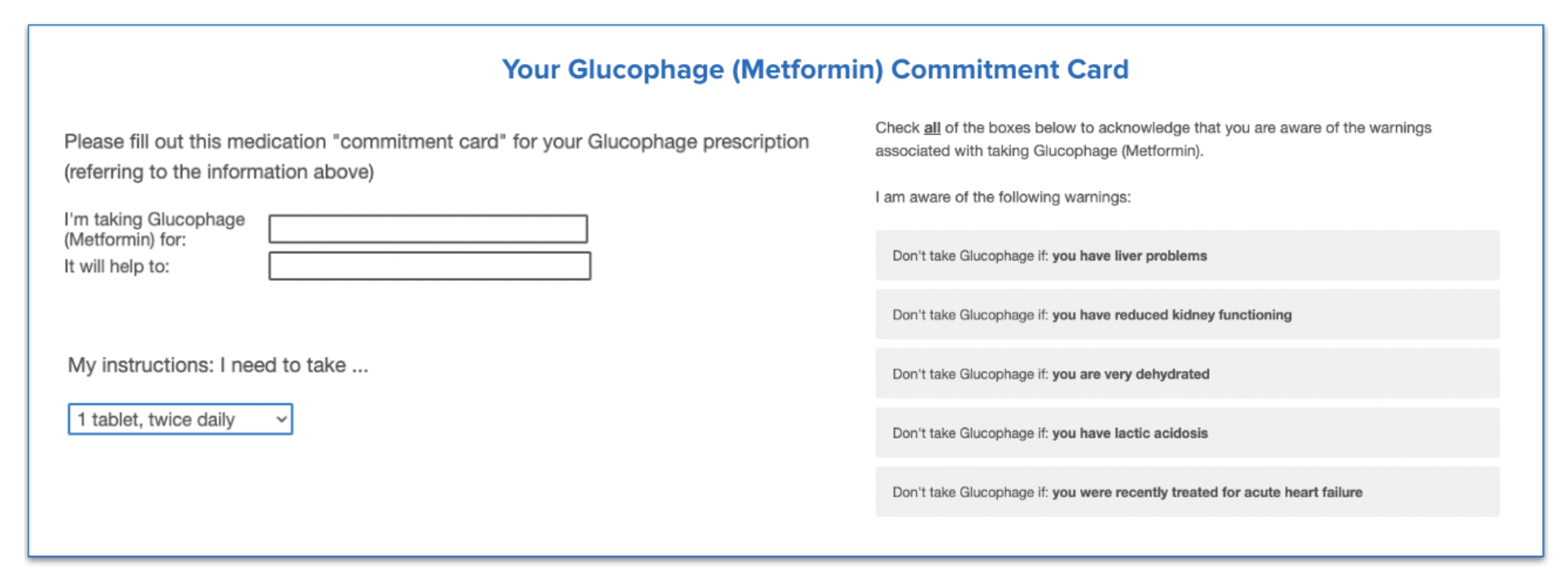

For our ‘good friction’ condition, we designed a prototype ‘commitment card’ that participants in our study were required to fill out for each medication. This encouraged participants to slow down and reiterate the key information in their own words. After all, research suggests that note-taking allows people to better remember the things they read.

How We Designed Our Experiment

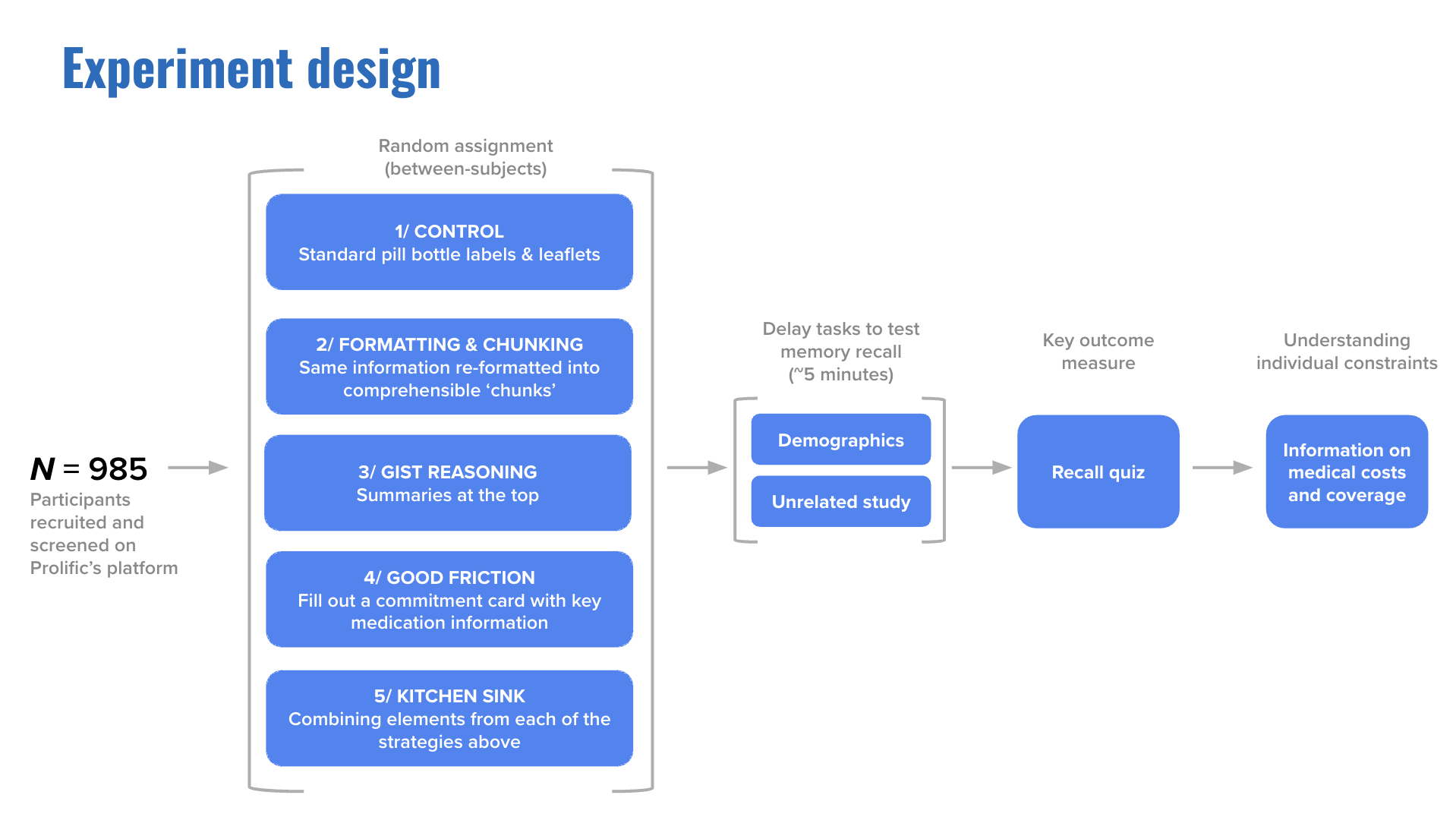

To put these strategies to the test, we partnered with Prolific to recruit and screen participants, and recruited a sample size of 985—all US residents who took at least one prescription drug per week.

First we showed participants a pill bottle label and leaflet for three common medications: Metformin, Atorvastatin, and Levothyroxine. Then we distracted them with an unrelated task, and afterwards asked them to recall the information on the label: What was the name of the drug? What were the side effects? We tested four different versions of the label and had one control strategy, which was a standard prescription label. The measure for the experiment was how well people could remember prescription content. This served as a proxy for how effective the label would be in the real world as opposed to in a study.

Participants were divided into five groups.

Control Group

Participants in our control group received a prescription label and leaflet that looked almost identical to those used by CVS and Walgreens.

Formatting and Chunking

This condition used interventions similar to those used in existing medical research. As mentioned above, we used icons, simplified language, and highlighting to reorganize the labels into more readable chunks.

Gist Reasoning

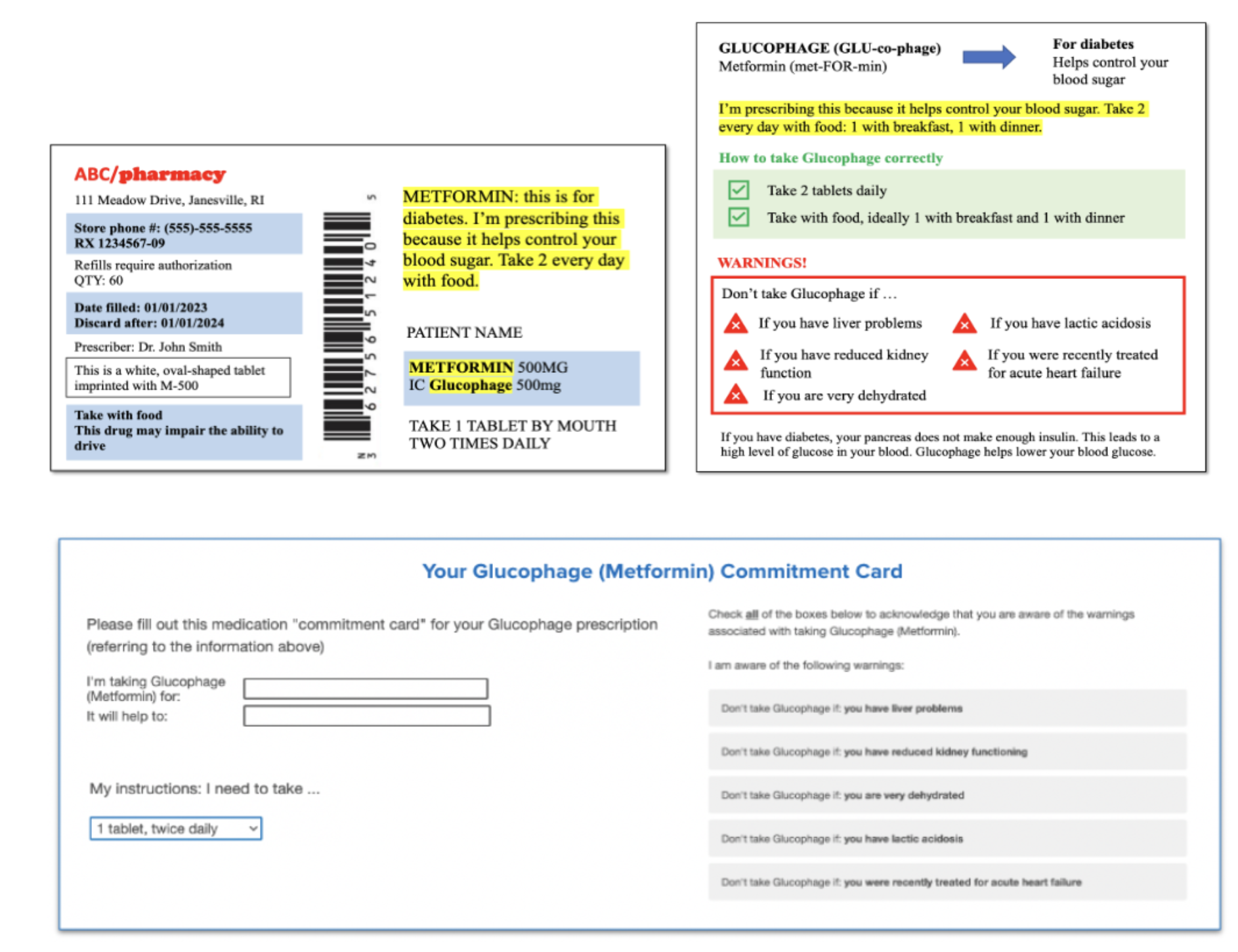

For the ‘gist reasoning’ condition, we designed a prescription label and leaflet that highlighted the ‘gist’ in a summary at the top, highlighted in yellow.

Good Friction

The ‘good friction’ condition used the exact same labels and leaflets as the control group, but asked people to actually write down the key information via the commitment card for each medication.

Kitchen Sink

The ‘kitchen sink’ condition included elements from each of the other conditions. Participants in this group received reformatted, more patient friendly labels with the ‘gist’ at the top and a commitment card for each medication.

The Big ‘Aha’: Adding Friction Significantly Improves Medication Recall

The results?

We found that compared to the control, typical interventions tested by medical researchers, like making labels and leaflets more patient-friendly, had no impact on patients’ ability to recall information about their medication.

Similarly, our ‘gist reasoning’ strategy also had no impact on recall (not by itself, anyway).

Our ‘good friction’ strategy, however, led to an 11% improvement in recall. And our ‘kitchen sink’ strategy led to even more exciting results, improving recall by 17%.

Everything But the Kitchen Sink

Aptly-named, our ‘kitchen sink’ strategy involved combining elements from each of the other strategies. This meant:

- Adding ‘gist’ summaries.

- Reformatting labels and leaflets to make them more patient-friendly.

- Including a ‘commitment card,’ identical to that used in the ‘good friction’ strategy.

In other words, we threw everything we had at the problem — everything but the kitchen sink. And it paid off big time.

Where Do We Go From Here?

It’s time to break the universal rule that friction is a bad thing, and add some nuance to it.

Adding friction can significantly improve short-term medication recall, and may even have benefits for adherence and medication error rates. So why does it work?

On average, we found that the ‘good friction’ and ‘kitchen sink’ strategies slowed participants down by 4 minutes compared to the control, the ‘commitment card’ adds value all on its own.

While adding ‘good friction’ works in part because it slows participants down, the commitment card improves recall over and above the effects of increasing time spent on the labels and leaflets page alone.

As a practical application, we think this opens the doors for future medical research to explore other forms of friction in other health contexts, and even examine how to improve medication recall in the long-term.

In the future, pharmacies could provide ‘commitment cards’ alongside prescriptions, and digital health apps could incorporate friction to improve user experience, convey their value, and meaningfully improve medication recall among patients.

This is one example of how we used our process to change behavior meaningfully through small interventions. We can help your health, finance, or tech company unlock big impact. Get in touch to learn more about our consulting services. Or learn more behavioral science by joining one of our bootcamps.