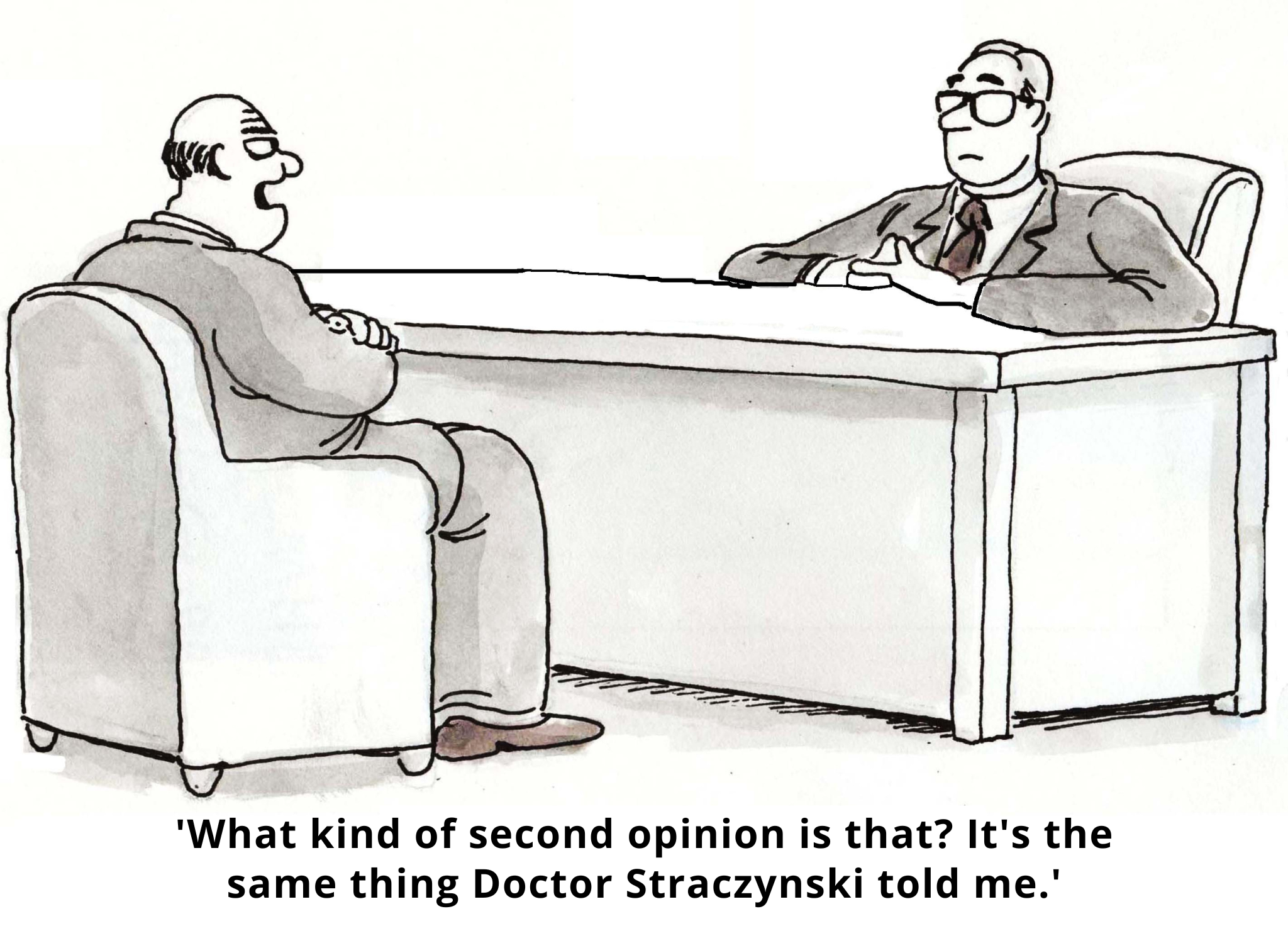

Imagine that you went to three different doctors for chronic ankle injuries. The first one recommends surgery on your right foot. The second proposes custom orthotics. And the third? She wants to prescribe a boot for your left foot.

One injury, two ankles, three doctors, and three very different approaches to treatment. What’s happening?

When it comes to making healthcare decisions, behavioral science has shown us that we’re only human. In other words? We’re irrational. But what about the medical experts who treat us? Surely they’re more reasonable decision-makers?

Unfortunately… no! Clinical decision-making is a fast-paced, emotional, and social activity, and as such, it’s susceptible to cognitive bias. This bias is increasingly recognized as a source of medical errors in clinical practice. It turns out that physicians and other experts are human too, and thus prone to irrationality in their treatment and prescribing decisions.

The good news? Behavioral science can help.

Below, we outline three important decision-making biases that impact medical experts – and suggest behaviorally-informed interventions to improve patient care.

1: Behavioral Inertia (Status Quo and Omission Biases)

Status quo bias predisposes us to stick with things as they are rather than actively initiate change to break old habits. Like us, doctors avoid direct action when possible and tend to favor their current practices and default options.

Status quo bias can be seen in all kinds of clinical situations. For example, among multiple treatment options, clinicians are likely to favor the most ‘automatic’ one. Case in point: one research study found that physicians with an order entry system that automatically defaults to generic drugs order generics at higher rates than brand-name medications. Why? Because it’s the default choice.

Clinicians’ behavioral inertia can also contribute to diagnostic errors. For instance, patients are sometimes labeled with an incorrect diagnosis early in their presentation. Diagnoses are difficult to remove once attached – and may seal a patient’s fate. Doctors usually read patients’ charts before seeing them. So, if a colleague in the ER has already written a note with a diagnosis hypothesis and started a treatment plan, it’s very hard to look at the patient with an unbiased eye.

But doctors don’t just stick with the status quo because it’s easier. They may also be reluctant to actively change a patient’s treatment because of ‘omission bias.’ This refers to our tendency to (inappropriately) judge harms we cause through inaction as less severe – or blameworthy – than those we cause directly. And when coupled with the taboo trade-offs often associated with healthcare decision-making, omission bias can nudge doctors towards inaction.

Solution A: Create Thoughtful Defaults

Faced with many treatment options, doctors tend to favor the most automatic one. One strategy is thus to establish the desirable clinical behavior as the passive, default option for clinicians’ decision making – the one invoked if no active choice is made to change course.

Solution B: Pre-commit to Change

It’s hard for us to break from the status quo in the heat of the moment. But when asked to commit to changing a future action, we’re more amenable.

For instance, one experiment conducted in a clinic explored the impact of a public commitment poster to reduce the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. This reminder of the doctor’s signed promise to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was displayed in their examination rooms for three months. This reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for up to 12 months at follow-up. The lesson? Doctors can change their behavior when their errors are made salient, they pre-commit to change, and they’re reminded of their commitments.

2. Social Norms and Social Desirability Bias

Research on social norms has shown that we’re more likely to follow the herd – at least, to the extent that we perceive the herd as sharing our circumstances. In fact, our decision of whom to follow is not random and is often associated with status. For doctors, this means knowing that they’re fitting in with the existing social norms of physician peers and experts in their field.

For example, doctors are likely to consider: Are other doctors following these updated guidelines? Are other doctors trying this new medication with their patients? What do other doctors think about the results from this clinical study? And these perceptions influence their behavior.

Solution: Salient Peer Comparisons

There are a number of potential strategies to give individual doctors clear direction about social norms regarding the desired behavior. One way to really boost this signal is to leverage the strategy of peer comparison feedback, as demonstrated in an experiment designed to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.

In this experiment, doctors received a monthly email informing them of their performance relative to their peers. Those with the lowest inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rates were congratulated for being ‘top performers.’ Doctors who were not top performers, by contrast, were told, ‘You are not a top performer.’ The email also included a personalized count of antibiotic prescriptions and the count for a typical top performer. The result? Inappropriate prescribing dropped from 19.9% to 3.7% by the end of the study.

3. Cognitive Overload and Limited Attention

People only have a limited amount of mental bandwidth and attention to devote to decision-making. Doctors working in busy clinical settings, who often need to see patients back-to-back, quickly, all day, are no exception!

Research suggests that even simple complexities can impact physician treatment decisions. Redelmeier and Shafir presented doctors with a patient case study that read something like, ‘here’s a patient, he’s a 67 year old farmer that has been suffering with right hip pain for a while. A few weeks ago you decided that nothing was working for this patient, so you referred the patient to have a hip replacement.’

At this point in the study, the doctor believes the patient is on the path to get his hip replaced. Then the researchers presented one of two scenarios. In the first, doctors were told that the researchers had reviewed the patient’s case on the previous day and realized they had forgotten to try one medication: Ibuprofen. In the second scenario, doctors were told that the researchers had reviewed the patient’s case and realized they had forgotten to try two medications: Ibuprofen and Piroxicam. So, what happened?

More doctors suggested holding out on the surgery and trying a medication in the first scenario, when only one medication was recommended. Why? Because in the second scenario, it’s easier to move forward with hip replacement than choose between trying Ibuprofen or Piroxicam. Comparing three options is so mentally demanding that doctors simply chose the default option – thereby avoiding the cognitive effort required to evaluate which drug to prescribe. So they stuck with the status quo – in this case, keeping the patient off medication.

Solution: Choice Simplicity & Timely Reminders

Clinicians are human. As such, they’re hard-wired to make decisions in ways that lessen cognitive burden. But we can reduce that burden by streamlining recommendations and simplifying choice.

Moreover, sometimes – despite the best of intentions – doctors forget to act in the moment due to limited mental bandwidth. But it turns out that simple, timely reminders can help them overcome issues caused by limited attentional resources. As for the best time and place to send these reminders to doctors? Any time when they can immediately execute the task at hand. Simplified just-in-time reminders and memory cues – such as reminder-based systems embedded in EMR charts – can help overcome issues of limited attention.

Wrapping Up: Behaviorally-Informed Environments Mean Better Clinical Decisions

Physicians are highly skilled at synthesizing clinical evidence into treatment decisions. But, just like the rest of us, they deviate from making rational choices in predictable ways. With a better awareness of these decisional biases, clinicians can use behavioral science strategies to improve their decision-making environments – and increase the likelihood of optimal clinical decision-making.

Need help solving physician-related (or other) healthcare challenges? Contact us – we’d love to chat! Or learn more behavioral science by joining our health bootcamp.