Using Social Proof to Change Spending Behavior

This project is a part of Duke’s Common Cents Lab. The Common Cents Lab is funded by the MetLife Foundation and supported by Blackrock as part of BlackRock’s Emergency Savings Initiative.

Overview: State of the Credit Union

Arizona Financial Credit Union has 150k+ members spread across the state. And like most credit unions, they think deeply about helping their members succeed financially.

However, when your income needs to stretch across the month, succeeding financially is easier said than done. Given that most of us can’t magically increase our income, AZFCU knew it needed to help people manage expenses.

In 2017, they came to Duke’s Common Cents Lab, a lab co-founded by Irrational Labs’ Kristen Berman, and asked for help. Through qualitative interviews and in-product testing, Common Cents Lab drove a deeper understanding of their user’s relationship with money—and ultimately an expense reduction.

The Approach: Bridge the Gap Between What People Say They’ll Do and What They Actually Do

People say they want more money at the end of the month. But the same people also tend to like spending money today.

It’s clear that addressing this disconnect between people’s stated goals and their actions requires a behavioral approach that considers the psychological factors contributing to decision-making.

To gain deeper insights, the team conducted a behavioral diagnosis: an end-to-end product audit along with archival and federal data analysis, a literature review, and user surveys. By understanding the behavioral biases at play, they could develop interventions to nudge individuals toward making choices that prioritized their financial well-being.

Key Insights into How Social Proof Impacts Spending

What did our behavioral diagnosis uncover? We found two key insights.

People Underestimate Their Own Expenses

Ask anyone what they spend on dining out and they’re likely to self-report lower numbers than their bank statements show.

People Overestimate How Much Their Peers Are Spending

In fact, people thought others were spending more than them across all 11 spending categories. This is likely a result of two psychological phenomena:

- The “better-than-average” effect, which shows up most strongly on actions that are easy, common, and controllable, like restaurant spending.

- The availability heuristic, such that people use visibility as a proxy for actual frequency. Since at-home dining is relatively invisible, the assumption becomes that dining out is frequent.

And because people generally don’t talk about money, there are few good mechanisms for correcting this overestimation.

The Experiment: Tweak Social Norm Messaging

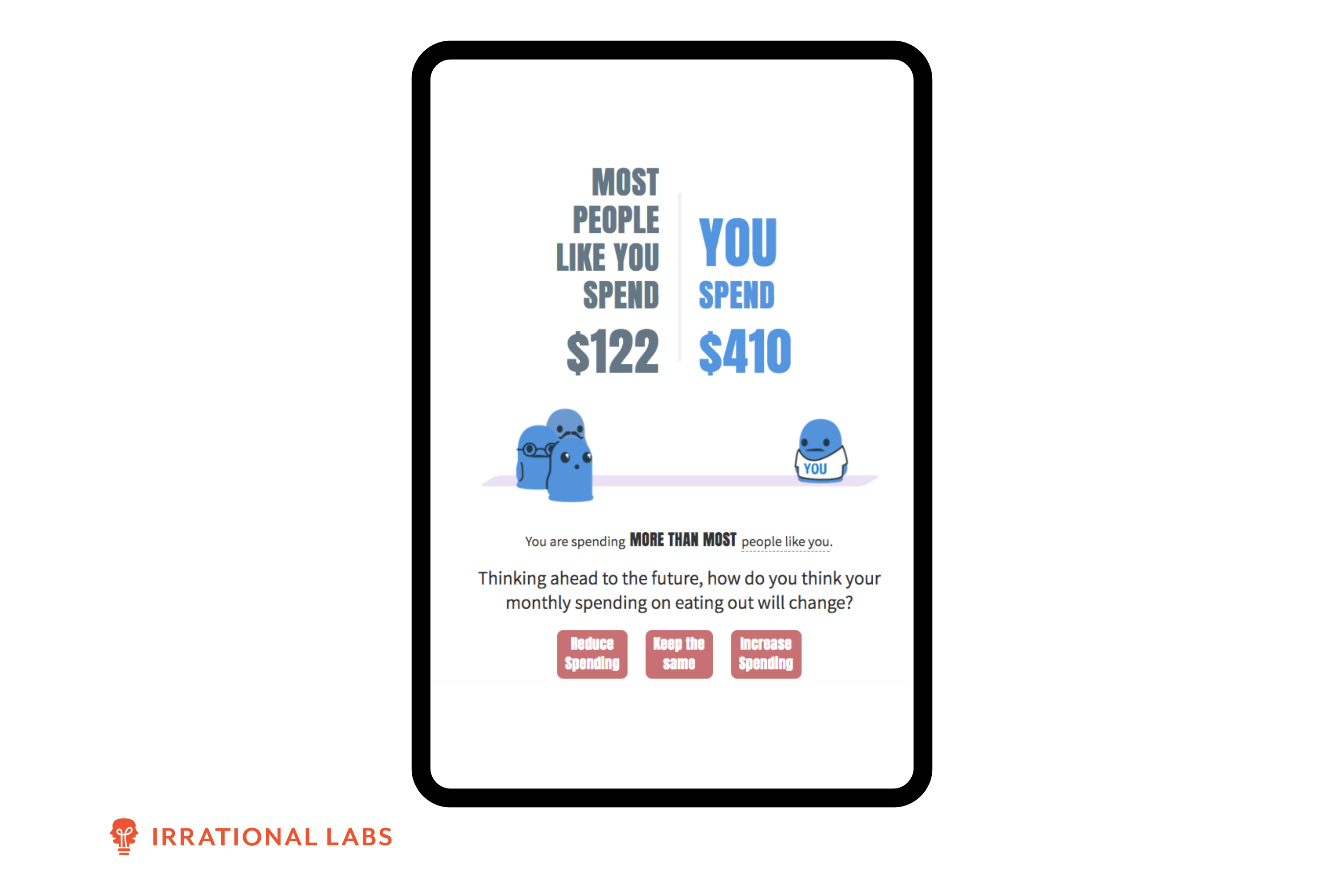

To put this question to the test, 8,000 members of AZFCU were offered the chance to estimate their monthly eating-out spending via an email. They were then told what they actually spend, relative to what other people spend. As a control, an additional 3,000 members were not sent the email.

The team of behavioral scientists at Common Cents Lab drove the design, working directly with PMs and engineers, and analyzed the data to report on results.

So, what did they learn?

AZFCU Case Study: 4 Lessons

Here are the key takeaways from our experiment.

Lesson 1: Use Curiosity in Subject Lines

With the words, ‘Curious what people like you spend?,’ the experiment achieved a remarkable 22% click-through rate, significantly surpassing AFCU’s average engagement. Learning: Curiosity (especially about others’s spending!) is definitely a way to catch attention.

Lesson 2: Users Think They’re Better Than Other Users

People think they spend less than everyone else. In this experiment, people guessed that others were outspending them by approximately 18%. The implication is that they may not readily accept help – since they probably don’t think they need it.

Lesson 3: People Don’t Like Being Told They’re Doing Worse Than Their Peers

When they were told the truth about how much they were actually spending, they didn’t like it. And not surprisingly, they left. Around 58% of people who were told they were spending more than their peers abandoned our experiment.

Lesson 4: Help People Build The Plan For Change

At the end of the experience, users created implementation intentions—clear plans of action that facilitated follow-through—by choosing 2-3 specific strategies to reduce their spending from a list of tips. Within the following two weeks, these participants reduced their spending by an average of $17. But it wasn’t sticky enough. And before long any positive change to spending habits had worn off.

Lesson 5: Use People’s Motivation While You Have It

Habits are hard to break. And change doesn’t always last. An email 30 days ago likely won’t affect someone’s behavior today. In fact, it diminishes over time.

This group reduced their spending over the following month by $21. This was marginally significant (p=.06). The effect wore off in subsequent months. If you want sustaining change, you’d need more frequent interventions than a one-time social proof message Or to help people make one big change that reduces their spend over time—like canceling subscriptions.

Want to learn more about this work, or to partner with us to leverage behavioral science to solve your toughest financial services or other product problems? Contact us at [email protected].