This project is a part of Duke’s Common Cents Lab and is generously supported by MetLife Foundation. Common Cents Lab works to increase the financial health of low-to-moderate-income Americans. This project was led by Irrational Labs’ Richard Mathera.

BACKGROUND

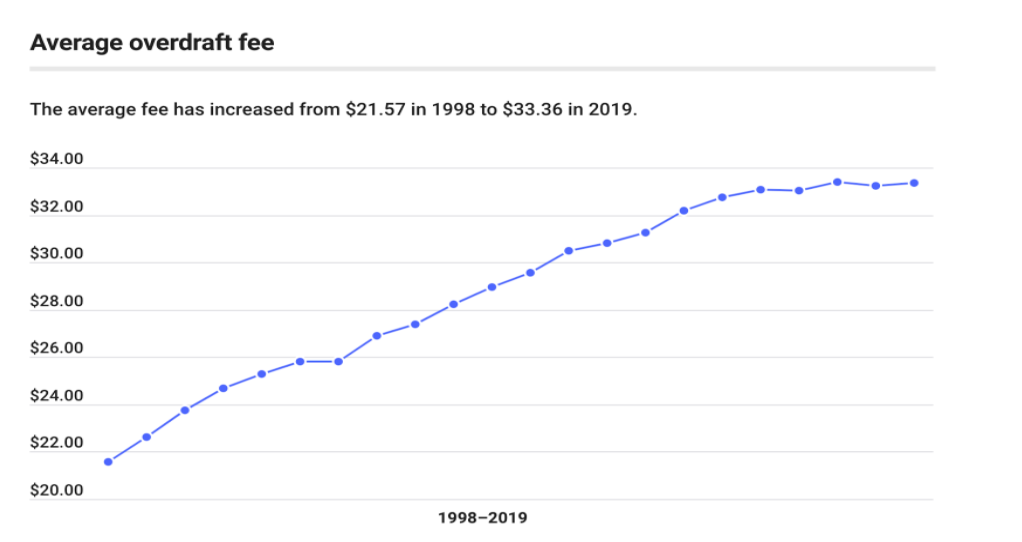

Almost all overdrafts (90%) are unintentional. Worse yet, they’re most often not a one-time mistake. Most Americans overdraft more than once per year, with 54% overdrafting 2-5 times, and 14% overdrafting 6-10 times. And, it’s not getting any better. Americans paid over $34 billion in overdrafts in 2017. Average overdraft fees have steadily risen from $22 to $34 per overdraft in the last 20 years.

https://www.bankrate.com/banking/checking/checking-account-survey/

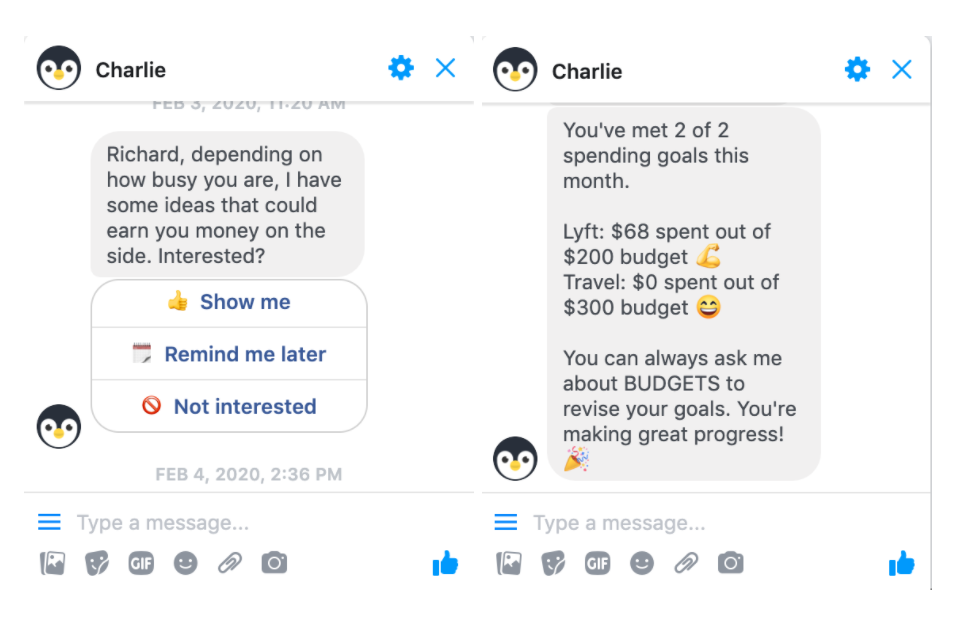

If given the option, most people (75%) would want their overdraft transactions declined. Fin-tech app Charlie, which focuses on helping people better manage and improve their finances, wanted to help its users reduce overdrafts.

To achieve this goal, Charlie teamed up with Common Cents Lab (CCL) and Irrational Labs to design an experiment aimed at finding the most effective way to help users reduce or avoid overdraft fees.

Example of an interaction a user may have with Charlie:

KEY INSIGHTS

In the current banking climate, there are a few ways people can avoid overdrafts:

-

- Link your savings account: Have a different account automatically cover the overdrafting account. However, this necessitates a non-zero balance in the covering account and may result in an overdraft transfer fee.

-

- Monitor account balance: Monitor your account balance. However, this requires timely information often not processed quickly enough by banks.

- Change banks: Change banks to an institution that doesn’t charge overdraft fees.

-

- Opt out of overdraft protection: When you opt out of overdraft protections, your overdrafting transactions will be declined.

Our team narrowed in on the last two options. These options are both one-time decisions a user can make that will have long-term effects on reducing their total fees. Ultimately, we prioritized “opting out” as the recommended path for most Charlie users because it is a simpler action than changing banks.

Opting out, however, isn’t inherently easy. We investigated the opt out process at a variety of popular banks and identified behavioral barriers a user would face, including:

-

- Confusing language: “Opting out of overdraft protection” is intuitively difficult to understand. Terms like “overdraft protection” and “overdraft coverage” are often conflated but mean different things.

- Opt out is framed as a loss: Banks say things like, “[You may] still face returned item fees”, “we will void your ATM privilege”, or “you lose free checks.” One bank told us we were about to “downgrade” our account.

- It’s just hard to do: Banks use logistical friction to make it hard to opt out, requiring multiple clicks and, in some cases, even a phone call.

EXPERIMENT

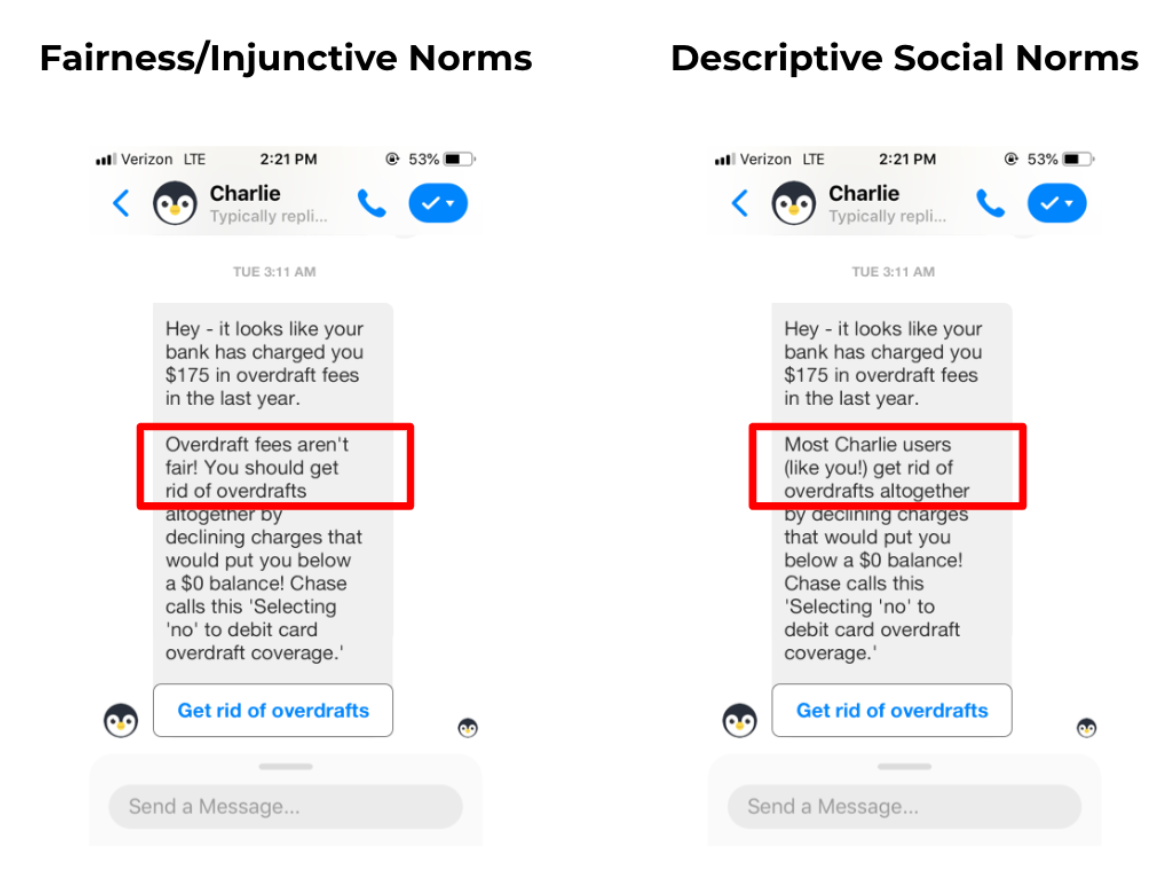

To overcome the above roadblocks and reduce overdrafts for users, Charlie and CCL tested two overdraft opt out messages against each other and a control of no message. In all three conditions, Charlie users received a message anytime they overdrafted. Messages were sent out to 4,000 Charlie users in a randomized manner.

The experimental opt out conditions drew upon the following two frameworks:

- Fairness and injunctive social norms: “Overdraft fees aren’t fair! You should get rid of overdrafts altogether…”

- Descriptive social norms: “Most Charlie users (like you!) get rid of overdrafts altogether…”

We sent both an initial message and a reminder message using these conditions. All messages had an opt out button that linked to the opt out page of the user’s bank.

RESULTS

We found that intervening with opt out messages was successful. The experimental conditions resulted in a net overdraft reduction of ~$23 per person (p < 0.05). A $23 reduction in overdraft fees equates to a 9% reduction in people’s total annual overdraft fees. The experimental intervention reduced gross overdrafts by ~$20. (p < 0.067)

Net Overdrafts Gross Overdrafts

(Overdrafts + Refunds) (Overdrafts without Refunds)

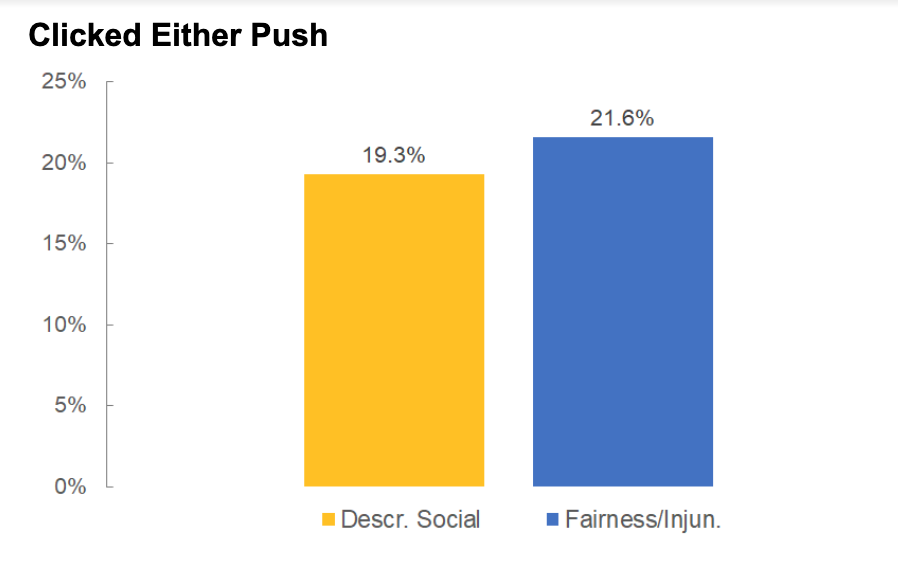

While both experimental conditions reduced overdrafts, there was no statistically significant difference in the success of the two messages. Around ~20% of users in both conditions clicked the initial message. For reminder messages, however, the fairness-and-injunctive-norms condition was significantly more successful, resulting in more clicks.

% of people who clicked either first push notification or reminder push notification

This overall effect was primarily driven by the treated group. People who clicked on the opt-out button had lower gross overdrafts by ~$36 (p < 0.011). However, we also found a benefit for those who didn’t click through opt out messages. While this group did not lower gross overdrafts, they did pursue refunds more frequently, resulting in an average of $5 more in refunds than the control group.

IMPACT

This intervention saved ~$75,000 in overdraft savings over the two month experimental period alone. If this was rolled out to the U.S. at scale, we’d save Americans $594,294,460 .