This project was led by Irrational Labs’ Richard Mathera and Isabel Macdonald.

Overview

Members of Credit Karma’s product, design, research, and analytics teams partnered with Irrational Labs to leverage behavioral design to improve member and product outcomes with Credit Karma Money Spend, Credit Karma’s new checking account.

First, we conducted an in-depth behavioral diagnosis to identify the greatest opportunities for behavioral design to improve the product. Then we designed, prioritized, and launched 4 behaviorally-informed interventions aimed at removing barriers to and increasing the benefits of funding the checking account.

In one of the four interventions, we identified timing-related friction. While we couldn’t eliminate the friction associated with that specific moment, we instead used the moment to help people avoid future friction – by encouraging automatic funding of their Credit Karma Money Spend accounts. This led to an 18% increase in recurring transfer setups and a significant increase in direct deposit interest.

The Problem

A behavioral diagnosis involves identifying behavioral barriers, friction, and critical behavioral biases involved in a process. Our behavioral diagnosis revealed a timing barrier: it can take several days for deposits transferred from another bank to Credit Karma to become fully available. This means members potentially wouldn’t have access to needed funds during that time – especially if they forget to make a transfer until the last minute.

Automatic bank transfers can help members avoid this challenge by decreasing the hassle of remembering to make transfers and ensuring their account is funded when needed.

Members can also set up direct deposits to their account. A special feature of the Credit Karma Money Spend account is that Credit Karma will post direct deposit funds to the account up to two days before payday. Members who take advantage of this feature avoid the transfer delay AND get their money up to two days earlier. Direct deposit also enables Credit Karma to have a longer and more consistent relationship with members.

In light of this, we designed an experiment to answer the question: How can we use moments when members experience friction to offer them a choice that eliminates that friction in the future?

The Experiment

We targeted the moment when members were likely to first become aware of the friction of bank transfer times, namely when they set up a first one-time bank transfer.

In the status quo experience, members were informed about this delay in full availability of funds and then redirected to the main checking account hub.

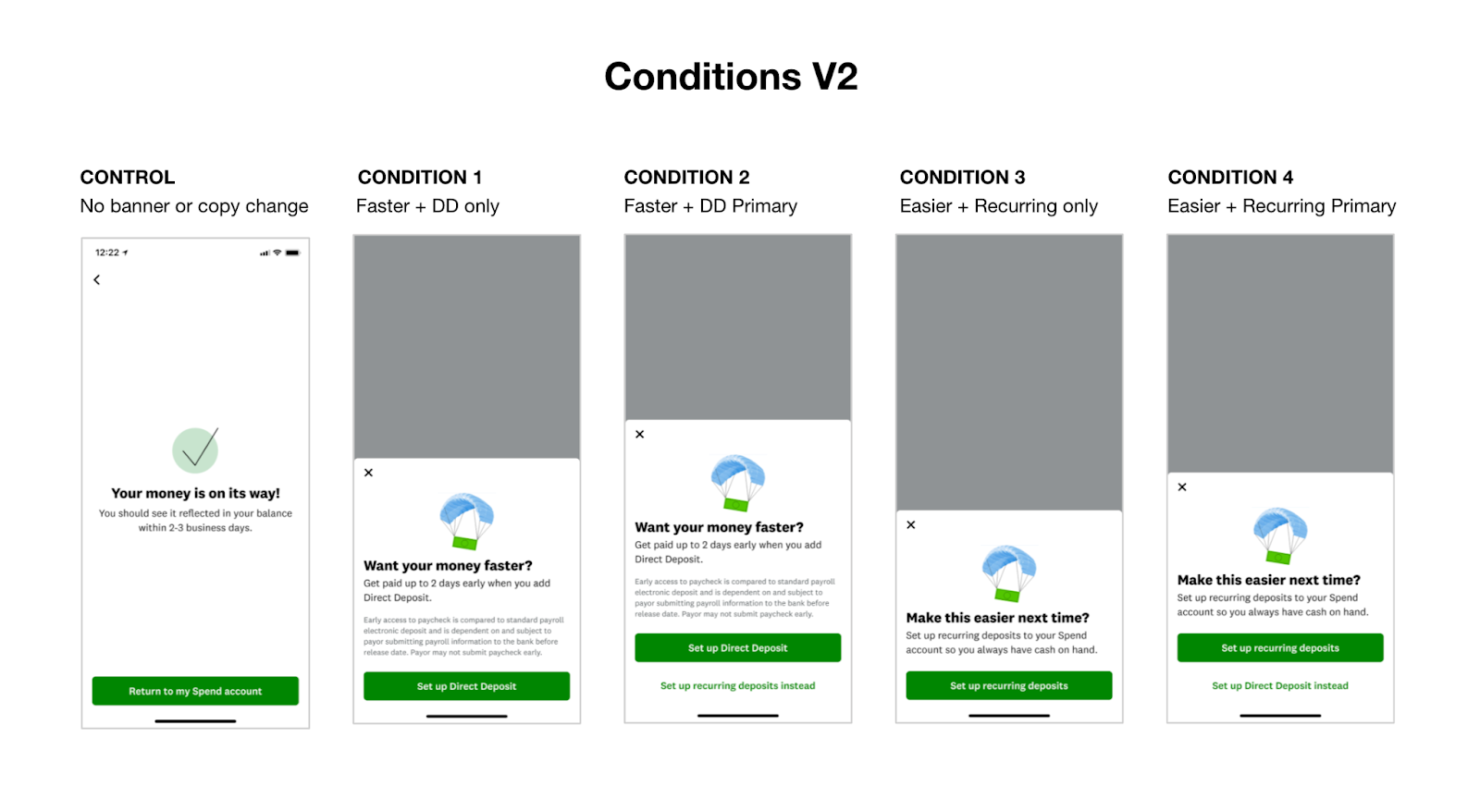

We compared the status quo control to four conditions that prompted different types of automated transfers before users returned to the hub:

- Direct deposits only

- Direct deposit as the default with a recurring transfer alternative

- Recurring transfers only

- Recurring transfers as the default with a direct deposit alternative

Condition D was the most successful condition – it drove a large increase (18%) in recurring deposit setups and a small increase in direct deposit setups. It also builds the mental model that direct deposits are an effective way to fund the account.

Lessons Learned

1. If you can’t resolve friction, see it as an opportunity

As behavioral designers, most often we identify sources of friction and seek to minimize or eliminate them. Since there isn’t an easy way to improve bank transfer processing times due to fraud concerns, we hypothesized that people might be annoyed by the friction in the moment and motivated to avoid it in the future.

2. Standardize experiment conditions as much as possible

Behavioral scientists know that people don’t often read a full paragraph or multiple lines of text. The first and most salient lines of text are usually the most important. We leveraged this insight and removed any extraneous factors to standardize our experimental conditions (such as consistently highlighting a benefit in the first line).

Experimental conditions

3. Include multiple variants, if sample size permits

Behavioral scientists know that when giving people multiple options, whichever option is first and/or more colorful/salient may be perceived as the default option. The differences in the messaging, “Want to make this easier?” or “Faster?”, could also nudge people towards one option or the other.

Initially, the team discussed three experimental variants: direct deposit only, recurring transfers only, or both. Many studies in behavioral science have found that defaults have a tremendous effect on people’s decision-making, so this was an important consideration when deciding which of these options to put first.

To test the difference between starting with direct deposits and starting with recurring transfers, an additional condition was added to the experiment after verifying that we would still be sufficiently powered.

4. Discuss trade-offs in outcomes before testing

When testing multiple experimental conditions, often different conditions lead to increases in different desirable outcomes OR to an improvement in one outcome and a negative effect on another.

To identify which condition “wins,” teams often need to consider trade-offs – such as whether each recurring transfer or direct deposit set up is of equal value to both the user and the business.

It is best to have these conversations beforehand to avoid being influenced by the results, and to make it clear to all members of the team what the next steps will be once the data is collected.

In this case, prior to the experimental launch, the team outlined different possible scenarios and agreed on the resulting next steps. For example, if condition A boosted direct deposits by more than 50 percent over condition C, condition A would dominate – even if condition C had a greater effect on recurring transfers.

————

Special thanks to the following Credit Karma team members for their collaboration in this partnership: Devon Alkire-Cussen, Kyle Thibaut, Satyen Motiani, Nicole Muther, Aakash Patel, and Tatiana Vlahovic.