I went to the emergency room (ER) 3 times in 2 weeks when my dad got sick. It was exhausting, frustrating, and overwhelming.

And after spending hours in a crowded waiting room, I couldn’t help but fantasize about what needs to change. Either we need to invest in improving the system and preventing recurring visits—or distract patients from their pain and wait time with a movie theater, popcorn, and puppies. Let’s start with the former?

ER Visits Are Tough—and Costly

The good news about unnecessary ER visits: preventing them is already front and center for health insurance companies. The bad news? They have yet to identify a solution.

I know this problem is top of mind for insurance companies because I work with a team of behavioral scientists. We help companies design systems that change behavior—and when insurance companies call us, they always ask how they can reduce unnecessary ER visits.

Why don’t insurance companies like ER visits? The biggest reason: they’re expensive. The average ER visit costs $1,404, compared to:

- $143 for an urgent care center

- $124 for a walk-in doctor’s office, and

- $49 for a telehealth visit.

Patients also detest ER trips—and between endless wait times and expensive medical bills, it’s easy to understand why.

So how can we fix this and get emergency rooms running more efficiently and effectively? And what can behavioral science bring to the table?

I have a few ideas—so let’s dive in, using my dad’s recent ER experiences as our lens.

My Dad: A Study in 3 ER Visits

As I mentioned, my sister and I recently took our dad to the ER 3 times (yes, really!) in 2 weeks.

Were these visits preventable? Let’s take a look:

- The first was a referral from my dad’s primary care provider (PCP). She wanted a CT Scan—and fast. It can take a week to get results when you go through normal channels (i.e. scheduling an appointment at an imaging center)—and that wasn’t fast enough.

- The second was for intense diarrhea and severe dehydration. My dad got IV fluids and a few tests—followed by discharge home.

- 2 days later, we brought him back for a third visit due to continued diarrhea and severe dehydration. He (once again) got IV fluids, a few tests, and a quick discharge.

My take: 2 of these visits could have been prevented—but not by my dad (or us) acting differently within the system. To prevent these visits, the system itself needs to behave differently. But how can we accomplish this?

Can Behavioral Science Interventions Help?

In behavioral science, there are 2 main types of interventions for different levels of behavior change.

One type of intervention is designed to work at the system level. For example, say your employer offers an automatic 401k enrollment. In this case, the system supports the behavior of saving for retirement—and this makes it easy for you to do the thing you want to do (i.e. save).

Another type of intervention is designed to work at the individual level. For example, consider nudges from employers (like emails or text messages) that remind employees to save for retirement. These interventions require individuals to behave differently within the current system—through their own actions.

Where Healthcare Gets It Wrong

The healthcare industry has mistakenly focused mostly on individual-level interventions in its efforts to reduce unnecessary ER visits. For example, insurance companies have considered denying coverage for ER visits that are not classified as true emergencies.

There are 2 underlying assumptions here: first, that patients know where to go for which ailment. Second, that monetary incentive will motivate them to preemptively learn these rules.

But is that really true?

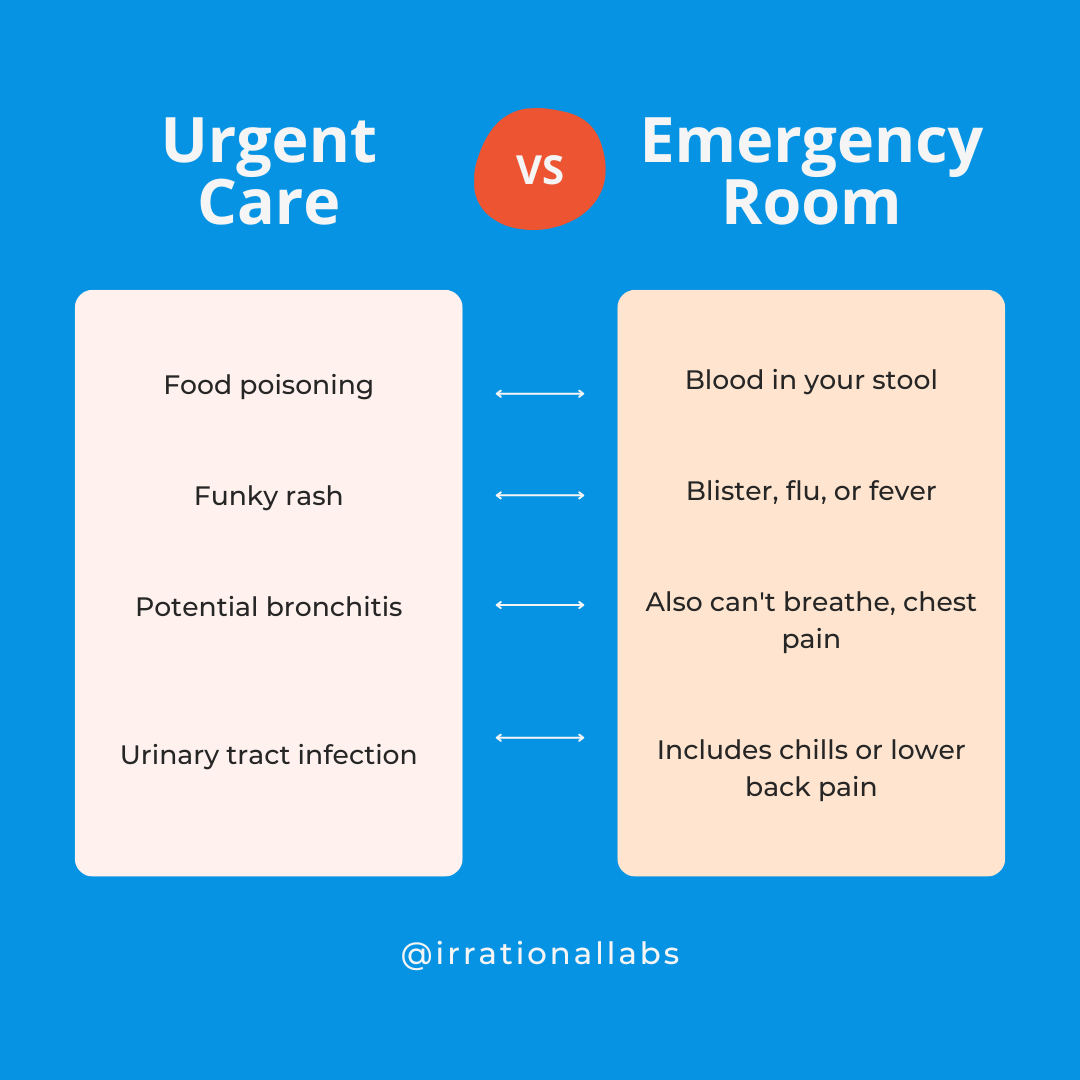

Let’s play out how this would look for a few common issues:

- Food poisoning? Urgent care. Unless there is blood in your stool—then ER.

- Funky rash? Urgent care. Unless you also have a blister, bruise, or fever—then ER.

- Potential bronchitis? Urgent care. Unless you have difficulty breathing or chest pain—then ER.

- Potential UTI? Urgent care. Unless you also have chills or lower back pain—then ER.

Confused? It’s doubtful that we’ll be able to train people to recognize these nuances, much less act on them when stress and discomfort are running high.

In other words: both this model and the infographic you see above are probably asking too much.

Individual-level interventions thus seem unlikely to reduce unnecessary ER visits. But let’s not throw in the towel just yet! System-level interventions offer a light at the end of the tunnel—and when the healthcare industry uses them, real change is possible.

For example, multiple studies have shown that lowering default order quantities for opioid prescriptions in the electronic health record (EHR) can significantly reduce the number of pills prescribed. So while telling doctors to ‘prescribe less’ doesn’t have an impact, adjusting defaults within the system does—likely because it makes the desired behavior change easy.

My Dad’s ER Adventures: A Look at System-Level Interventions

So, could system-level interventions have prevented my dad’s multiple ER visits? Let’s take a look, starting with the lowest-hanging fruit: what happens at discharge.

You may have noticed a common theme at the end of my dad’s ER visits: medical staff sent him home each time with little more than ‘goodbye and good luck.’ In other words, they put a band-aid on his symptoms and told him to call his PCP if further issues arose.

But no one asked if he actually had an appointment scheduled with his doctor. In fact, no one even asked if he knew his PCP’s name and phone number. So when further issues did arise, we landed right back in the ER. It was our quickest, easiest option.

The Path of Least Resistance (To Primary Care)

By making a different option the easiest, a system-level intervention could have prevented our (multiple) returns to the ER. In behavioral science, we call this type of intervention the ‘path of least resistance.’ If we want people to do a behavior, we need to make it the easiest thing they could possibly do—because when we make things easy, people do them more.

In my dad’s case, the desired behavior would be scheduling a follow-up appointment to address ongoing issues outside of the ER. And the ER could have reduced the friction involved—and made the process easier—in a few different ways.

Upon discharge, the ER could have scheduled a follow-up appointment with a PCP for 2-3 days out. Research has shown that facilitating follow-up appointments (i.e., with a patient navigator) can increase appointment adherence—and reduce return ER visits.

Of course, doctors are busy—and getting in quickly can be challenging. If this had been the case, maybe the ER could have facilitated a check-in appointment with a telehealth nurse. Or even better, they might have considered sending a home health nurse to follow up within 2-3 days of his first ER visit. While such services are pricey, 1 planned home care visit would have cost less than 2 more ER visits.

What a wake-up call to realize that hospitals are sending all these ER patients home without follow-up appointments! No wonder that as 1 study found, 24% of patients discharged from the ER return within 90 days.

In my dad’s case, he needed IV fluids, which primary care offices and urgent care facilities don’t typically administer. But 3 ER visits within 2 weeks and multiple phone calls finally drove his PCP to take action. She set up 5 days of home health visits for my dad. He got IV fluids at home—and he’s recovering. The downside: home health care costs an average of $26 per hour.

Can’t We Just Improve the Urgent Care Model?

You may be thinking the most obvious system-level intervention for reducing unnecessary ER visits is to improve the urgent care model. But can it really be this simple?

The answer: of course not. Healthcare is a complex beast to begin with—and the solution for improving our current urgent care model is far from obvious.

The basic intuition is to increase the number of urgent care centers in order to decrease ER visits. And this is correct—sort of. Having an open urgent care center in a given ZIP code reduces the total number of ER visits by residents in that ZIP code by 17.2 percent. But here’s where things get complicated: when we make something easier, more people do it (remember the path of least resistance?).

Having more urgent care centers means more people get care. Urgent care centers do decrease ER visits—but not by enough to offset the total cost increases of more people going to urgent care. And it’s not even a close fight: for every 37 urgent care visits, emergency rooms see only one less lower-acuity ER visit.

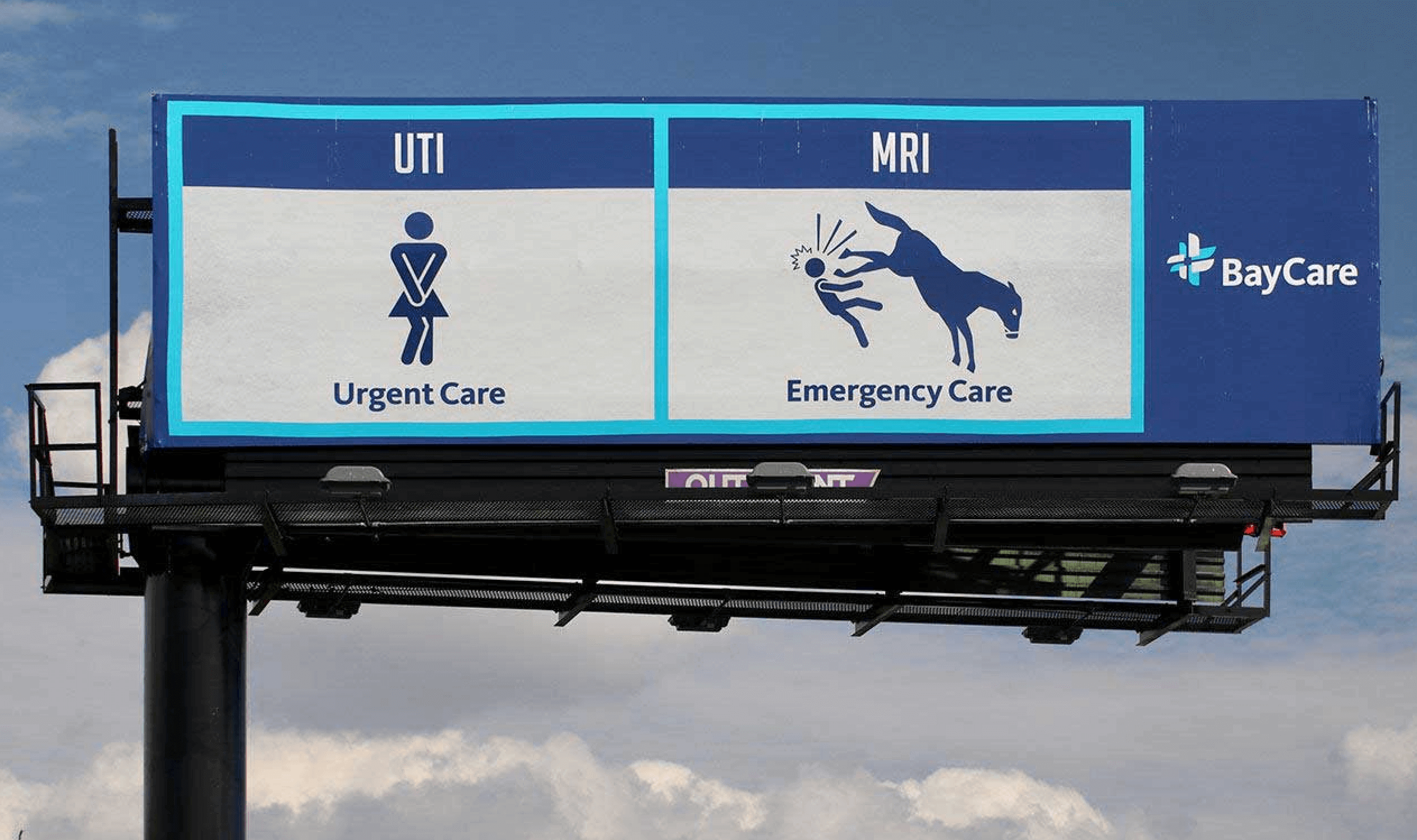

BayCare campaign to differentiate their urgent care and emergency care services (Devito/Verde; art direction & design: Nora Ryder)

Preventing Unnecessary ER Visits with Smarter System Solutions: Final Thoughts

While there’s no one easy answer to preventing unnecessary ER visits, there are countless possibilities worth considering, discussing, and testing. For example, could we:

- Compete with 911 and create an easy-to-remember national phone number for a nurse triage system?

- Incentivize diagnostic imaging centers to offer urgent appointments and faster results to higher-acuity patients?

- Locate urgent care centers next to ERs so that patients can be rerouted from ER triage to urgent care when appropriate?

- Give PCPs feedback loops for their referrals? In hindsight, if they could do it again, should they refer? Why?

- Proactively contact previous ER patients to get them set up with a primary care physician?

At Irrational Labs, we use behavioral diagnosis to better understand big problems, come up with ideas like these, and then design interventions to change behavior. We usually start at the system level. There are tons of opportunities for this—and we don’t stop asking questions until we get to the right ones.

We introduce small, systemic changes to make it hard for the humans in that system to do the wrong thing—because (let’s face it) we do the wrong thing a lot. And there you have it: yet another reason we should never rely on the patient to learn the difference between a scary rash and a really scary rash.

Need help solving challenges with your healthcare product or services? Get in touch to learn more about our consulting services. Or learn more behavioral science by joining our health bootcamp.