Would you be happier with 2nd or 3rd place? When does a competitor become a rival? And how do the supportive feelings you had for your teammates turn into antagonistic ones?

This week, in advance of the highly-anticipated Tokyo Olympics, behavioral scientist Lindsay Juarez walks us through the basic psychology of competition.

Coming in Second Place

If you’ve ever just missed your train and thought, “if only I’d made that light at the intersection,” then you’re familiar with counterfactual thinking—imagining what might have been. Now, what if it was the most high-stakes performance of your life and you could have pointed your toes a little harder during your dive to earn the gold medal instead of silver? Despite objectively performing better, athletes who come in second appear less happy than those who come in third.

The original paper for this finding used video from the 1992 Olympics and had participants rate the facial expressions and code the post-competition interviews of silver and bronze winners to see who acted happier. For example, they found that, on average, bronze medalists were a cheery 7.1 on a 1-10 “agony to ecstasy” scale while the silver medalists were more upset at 4.8, p < .001. The researchers also went out and interviewed 115 silver and bronze medalists at a regional athletic competition and found that the silver medalists reported more thoughts of regret and counterfactual thinking than did the bronze medalists.

A recent replication effort used updated methods (AI facial coding) and a larger dataset (winners from 2000-2016) to confirm this pattern of results. Gold medalists smiled the most (M = 3.07), followed by bronze medalists (M = 2.15), while at least on the smiling scale, silver medalists came in last (M = 1.10).

Please admire this perfect example of the phenomenon, in which the smile of Yohan Blake, the silver medalist on the left, pales in comparison to the smiles of Usain Bolt with the gold and Warren Weir with bronze.

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F., & Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 603-610.

Hedgcock, W. M., Luangrath, A. W., & Webster, R. (2020). Counterfactual thinking and facial expressions among Olympic medalists: A conceptual replication of Medvec, Madey, and Gilovich’s (1995) findings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000992

From Competitor to Rival

Sticking with the theme, this next pair of articles examines how competing with a rival increases motivation. Gavin Kilduff (2014) found that thinking about competing with a rival made people report higher motivation and better performances than did thinking about competitions with non-rivals. To confirm that rivals did actually change performance, he also collected 6 years of race data from a local running club, surveyed the runners to identify their rivals, and calculated whether the presence of a rival made a runner faster. It did. When a runner’s rival was in a race, the runner was 4.92 seconds faster per kilometer than their usual pace, p < .001. In a 5k, that would mean shaving about a half minute off your time—maybe enough to get you into second place!

So how does someone become a rival anyway? A different team of researchers conducted a series of 7 studies designed to untangle what elevates someone from a competitor to a rival and how that change in mindset changes the way people pursue their goals.

Put simply, rivals tend to be more familiar and similar to you than nonrivals, and you share a history with them. When you think about your rival and an upcoming competition with them, it feels like the competition is part of a larger story, stretching back into the past and forward into the future; it’s no longer just that one interaction. A nice example is the tennis player Roger Federer talking about his rival, Rafael Nadal, saying, “[I]it definitely becomes more and more special the more times we play against each other. […] every match we play from now on will be very interesting between us.”

The research team found that these legacy concerns about how a single competition fits into the larger story made players more impulsive and action-oriented. People were more likely to skip a practice round or give the intuitive but incorrect answer to brainteasers when they thought about their rivals and the legacy of competition. It also made people more interested in offensive rather than defensive strategies. This tendency could be adaptive, so that you’re raring to go and full of energy when it’s time to challenge your rival, but it also could lead to careless mistakes. If you’ve got a nemesis that you like to compare yourself to, make sure you think about them when it’s a well-practiced task.

Kilduff, G. J. (2014). Driven to win: Rivalry, motivation, and performance. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(8), 944-952.

Converse, B. A., & Reinhard, D. A. (2016). On rivalry and goal pursuit: Shared competitive history, legacy concerns, and strategy selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(2), 191-214.

Not Here to Make Friends

Let’s take a break from zero-sum competitions and rivals. How do you feel about people pursuing your same goal when everyone can achieve it, like losing weight or reaching 10,000 steps?

The researchers hypothesized that even in non-competitive contexts, people have complicated relationships with other goal strivers. They tested whether an individual’s progress and how certain success felt changed willingness to engage with others for moral and practical support.

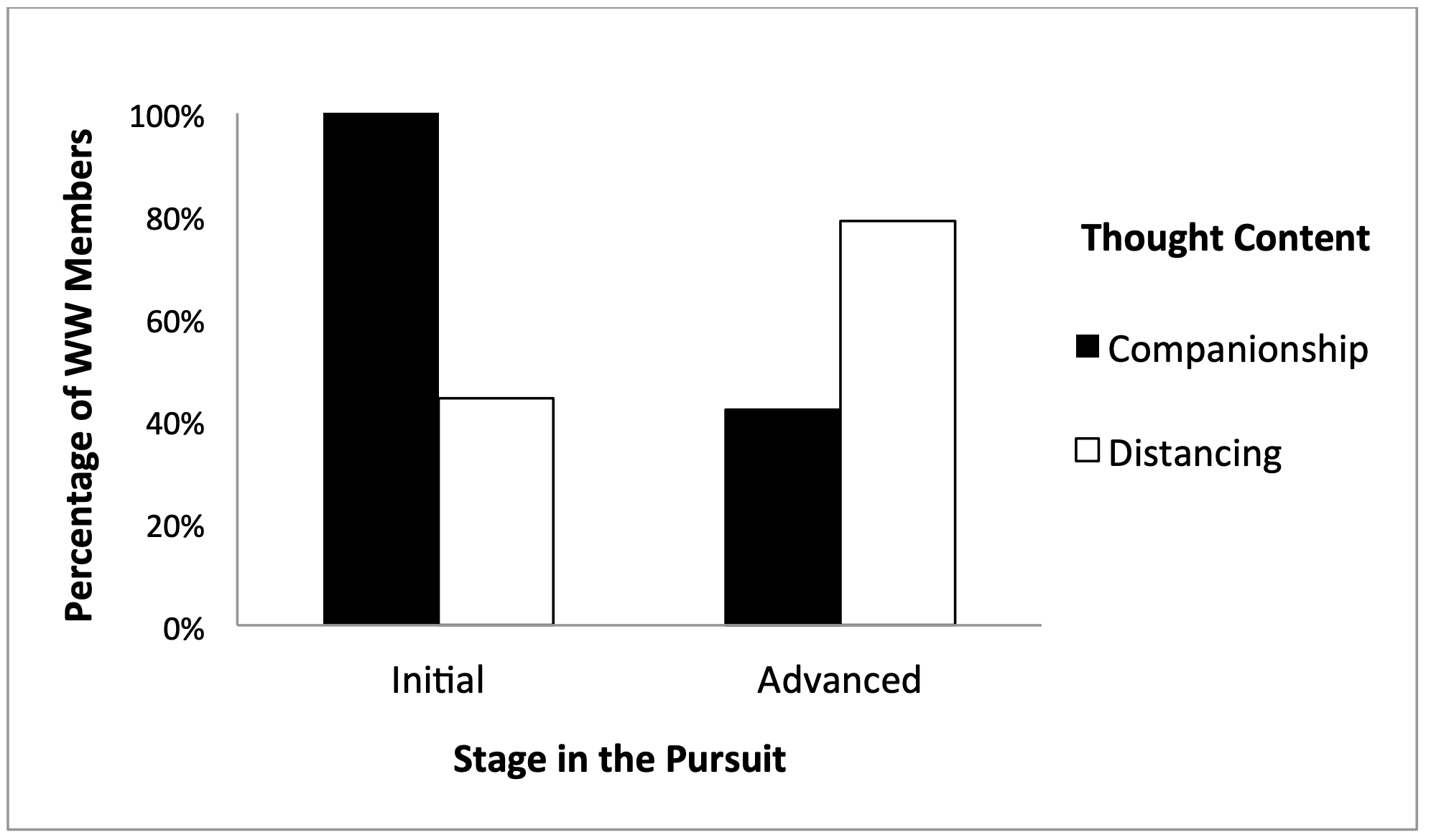

The first study in the set takes an interesting methodological approach. The researchers coded the transcriptions from 51 interviews and 143 group sessions from Weight Watchers participants to determine whether someone’s progress toward their goal weight was associated with being more or less friendly with their group members. Every single person who was in the initial stage of weight loss reported feeling closer to and wanting to share tips with their fellow members, while just 42% of those who were over halfway to their goal weight said the same. In fact, 79% of those in the late stage of weight loss said they felt distant from others and were reluctant to share information, saying things like, “I’m very close to getting to goal. I share a lot less now; I did all my sharing… ‘cause you know, I’m kinda at a different place.”

In their third study, researchers invited college students to participate in a step challenge, trying to hit 100,000 steps in one week. To understand the social dynamics in a controlled way, the students were matched to an ostensible partner whose progress they were updated on and who they could send motivational tips if they wanted. The partner also happened to be participating in the step challenge for the same or opposite reason (“health” or “appearance”) as the student. As is often the case, the partner was not real.

The researchers measured how close the real student reported feeling to their partner and how many words of advice they sent out as time went on. As theorized, people felt less close and helped less as they got closer to reaching their goal. But, this was true only when the partner’s reason for participating was the same; people sent equally long tips regardless of progress to partners with mismatched reasons.

To help explain this last twist, there’s follow-up research by this group on the importance of relative progress and our willingness to sabotage partners to stay ahead. Competition can be motivating, but there are definitely trade-offs. Cross your fingers that your Olympic favorites avoid second place, beat their rivals, and are friendly to their teammates.

Huang, S. C., Broniarczyk, S. M., Zhang, Y., & Beruchashvili, M. (2015). From close to distant: The dynamics of interpersonal relationships in shared goal pursuit. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(5), 1252-1266.

Want to learn more about behavioral design? Join our Behavioral Economics Bootcamp today.