Blank Post-Its.

Smart people.

Two days.

All of us zeroed in on a single question: How might we help low-income mothers improve their financial health?

I was at a human-centered design (HCD) thinking workshop led by a national nonprofit. The organization provided trained facilitators, detailed customer insights, proper brainstorming ground rules, and a creative space to fuel our energy.

Armed with insights gathered from dozens of interviews with low-income moms and at least five experts, we were tasked to come up with solutions. We followed the human-centered design process playbook to perfection.

Which solution ideas won?

After almost six months of interviews by the national non profit and two full days of brainstorming with the wider group, the top concepts that emerged included … drum roll …

- Emergency savings.

- A one-stop shop to get government benefits

- A central community space for gathering

These are good concepts. In fact, they’re great! They’re so great that they’ve been tried in dozens (if not hundreds) of communities before:

- Pew Charitable Trusts and Aspen Institute each identified short-term savings as a key focus in 2016 and 2017.

- The “one-stop shop” concept for public benefits has been tested in various forms across multiple countries with various funding models and to varying degrees of success.

- Brookings championed the “third space” in 2016 as a base component of community-building.

The 2-day long workshop and 6 months of work yielded no new ideas. This highlights two major flaws in human-centered design.

Flaws in the Human-Centered Design Process

What’s wrong with human-centered design? Let’s dive into the flaws of the process.

1. Human-Centered Design Under-Prioritizes Prior Insights

Over the last decade, the Human-Centered Design Process has contributed enormously to improving product development and design. However, this workshop highlighted one of its major flaws: It overemphasizes our own role in innovation (as in, us researchers).

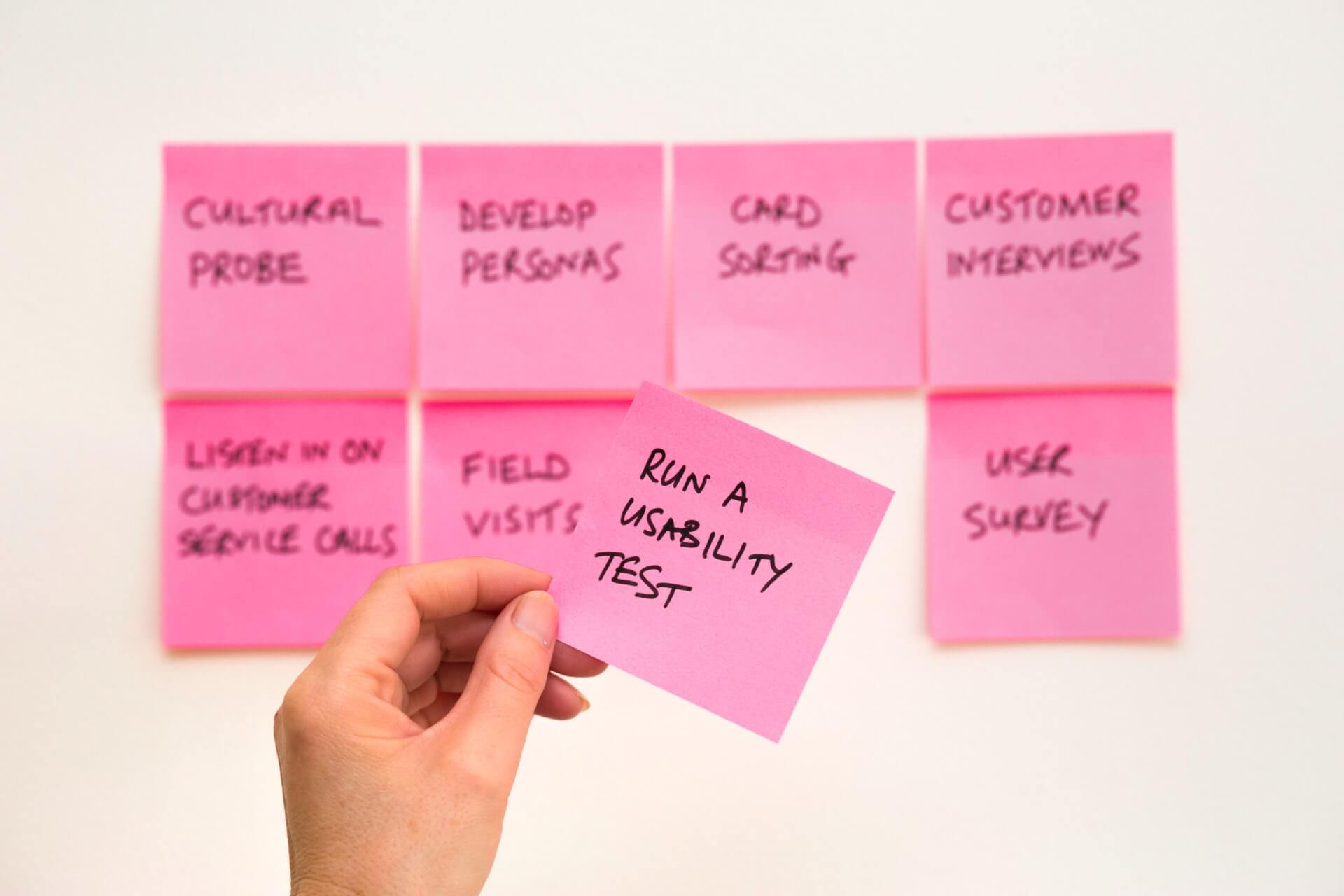

The Human-Centered Design process prioritizes generating ideas, rather than leveraging existing work. It’s a phase in the Human-Centered Design process where you and your team put up Post-Its to come up with new approaches to “How might we?” questions. This implicitly assumes your problem is new and that current solutions have failed so deeply you can learn nothing from them. It assumes you need to dig into your team’s creative soul to manifest a custom-built solution.

This is not human-centered design. This is self-centered design.

It’s why you can’t always trust your intuition.

By starting ideation from scratch, the human-centered design process effectively suggests your intuition is better than the experience of all prior designers, researchers and problem-solvers. Of course, for some people (Jony Ive? Elon Musk?), this might be true. But for the rest of us, behavioral economics research shows that many times, our gut instincts aren’t correct.

Intuition develops from repeated experience. Over time, you learn what works and what doesn’t. Imagine a chess player or a baseball player. Both get hundreds of moves or at bats over short periods of time. They adjust their behavior based on rapid feedback loops. Product Managers, Designers and Marketers lack this type of rapid feedback loop. We may launch 1 or 2 new products a year – if we’re lucky! More so, each solution we develop is likely wildly different from the other ones – or at minimum these solutions have varying constraints and random-ness.

Your new product launch may have flopped. Was it because of timing? Your sales channel? Your landing page? Another unknown variable?

Intuition is incredibly difficult to build if you have long feedback loops, but even more difficult to build if there is any noise and random-ness involved.

Of course, for experts, intuition can be helpful and relied on. It can be the key to coming up with successful insights. But pulling this life-long expertise out of experts during a group exercise around post-it boards? Not ideal.

2. Human-Centered Design Relies on an Unreliable Source: People

Imagine you’re interviewing a potential customer. You ask them what’s most important to them when picking a solution: To save time? To save money? To save the environment? It’s an important question. If you can get to the bottom of it, you can better design a solution that optimally meets their needs and effectively prioritize your roadmap.

The problem? Your customers “lie” to you.

No one says, “I’ll just do whatever everyone else is doing.” Yet this is actually what they do. In multiple controlled studies, social norms are found to be the bigger driver of behavior, not someone’s stated beliefs and preferences.

And consider Nisbett and Wilson’s study, in which people asked which of four different nightgowns they liked best. The order of nightgowns was randomized, but the majority of people picked the one on the far right. When asked why, participants came up with creative answers, but no one said, “because it was the last pair on the right.” (This is an example of an order effect.)

In systems like this, where people are unaware of their preferences, we can’t depend on their input or our own intuitions about what solutions will be optimal.

Humans Don’t Admit When We Don’t Know

Decades of work in psychology show that much of human behavior is guided by mental processes outside our conscious awareness. Simply put, we are unaware of what goes on in our brain, our susceptibility to biases, and how we make decisions.

Given we’re typically incognizant of our decision-making processes, you’d imagine questions about our decision-making should be met with answers like, “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure” or “I’m not all that confident.” What happens, however, is the exact opposite.

In a study we conducted with 496 people, we explicitly asked whether participants thought a default setting would influence their choices for organ donation and retirement savings, and how confident they were about this.

If people were aware of how much the environment impacts their decision making, we’d expect people to have lower confidence in their answers. Not the case. 71% of people who said the default would not impact their retirement or organ-donation decision were “very” or “completely” confident in their answer.

Not only do people avoid answering questions with uncertainty, they’re actually confident in their incorrect answers.

This in mind, things don’t look good for traditional approaches to studying people’s behavior. When you ask people questions about why they did something, it seems they unwittingly make up stories and justifications. And perhaps more concerning for researchers, they’re confident in the story they made up!

So where does that leave us?

How are we to create new products and features if we’re not only starting from scratch, but the traditional method of asking customers to gain insights frequently misleads us?

It turns out there’s a more scientific alternative to design thinking—one where we don’t have to start from scratch: Behavioral Design.

The Behavioral Design process guides teams to come up with ideas that take into account previous, high-quality ideas. It also prioritizes not what users say they’ll do, but what they actually do.

The Behavioral Design Process

Most of the time, people have attempted to solve the same problem you’re looking at, and then written about it in academic journals or case studies. Not only that, but they’ve rigorously evaluated the results.

This is why one of the starting points of problem-solving in behavioral science is a review of existing academic literature to inform hypotheses about how to solve a particular problem (or drive intuition about how particular solutions might fare).

Once we’ve leveraged existing knowledge, behavioral scientists conduct a behavioral diagnosis. This is a map of all the small details within the environment in question (i.e. a low-income mother’s financial reality). Its goal is to reveal the psychologies pushing people to act or not act in certain situations and understand what people actually do vs. what they say they do.

Ultimately, this happens because referees are determining that not doing anything is a better option than not making any call at all.

With these core inputs, we then generate hypotheses about how to solve a problem based on actual behavior. These hypotheses can then be tested both through quantitative and qualitative research, and typically provide a strong starting point for iteration.

The Behavioral Science Design Process: Examples

Now, if we apply these tactics towards designing new products and experiences, we have the beginnings of the behavioral science design process. It not only dramatically reduces the up-front effort required by teams, but it incorporates existing research on how people actually behave.

And, more importantly, it works:

- Google used it to increase retention in advertisers

- Steady doubled its conversion rates for a new feature

- Livongo used it to drive a 120% increase in registrations

Behavioral design can be applied anywhere. Want to create a new product to help students save money? Make your meditation app more sticky? Increase uptake of your city’s recycling program? Use behavioral design.

Looking for a more in-depth guide to implementing behavioral design to your research process and product? The Irrational Labs Behavioral Design Guide can help.

Looking for a more in-depth guide to implementing behavioral design to your research process and product? Check out our Behavioral Design online course.

—

Kristen Berman co-founded Irrational Labs with Dan Ariely. Irrational Labs uses behavioral science to design products that help people become happier, healthier and wealthier. Berman was on the founding team of Google’s behavioral economics team and was previously the founder of Duke’s Common Cents Lab, a behavioral economics lab focused on financial health.

Richard Mathera is a managing director at Irrational Labs, focused on using behavioral science to increase financial well being. Mathera was previously a senior researcher at Duke’s Common Cents Lab and a Senior Advisor at USAID’s Office of Development Credit.

Inspired by these insights into behavioral design and want to learn more?

Sign up for the Irrational Labs newsletter and never miss a blog post, podcast episode, or behavioral economics insight.

Want to learn more about behavioral design? Join our Behavioral Economics Bootcamp today.